The safety net, crime and budget priorities

"I’m hungry, I ain’t got no clothes, my brother’s locked up, my mother’s not doing nothing for me, so let me go do this.”

There is a strong consensus among Washingtonians that we should be doing everything we can to prevent crime while also fixing the enforcement problems throughout DC’s criminal justice system. Preventive policies outpoll even wildly popular enforcement policies with 90%-93% of voters supporting “proposals for addressing the root causes of crime” in this poll from Opportunity DC:

In overwhelmingly Democratic DC, voters tend to strongly reject the common-on-social-media polarized debate that forces a false choice between enforcing the laws and trying to redirect “at risk” people away from criminal activity. The “risk” of criminal activity correlates strongly with poverty, unemployment and related social ills but this can be easily misconstrued in the crime debate so it’s worth outlining some key facts:

The vast majority of poor people are not criminals and poverty is not a legal excuse for engaging in criminal activity

Some efforts to raise the salience of these “root causes” fall into the trap of rhetorically excusing criminal behavior or portraying a “everybody does it” stereotype of poor people and crime

Some criminals come from affluent backgrounds and/or have motives for crime (like retribution for insults on social media) that no amount of redistribution or safety net programs would realistically prevent their crimes

Poverty and related social problems are risk factors for crime and addressing these problems can help prevent crime in combination with enforcement efforts

Some crimes are directly a result of money problems; i.e. stealing food to feed one’s family or stealing goods for resale in order to pay rent

For other people stressors like poverty or untreated mental health/substance abuse issues cause them to be more likely to make bad decisions that include criminal behavior

Addressing these problems can reduce someone’s likelihood of committing a crime or even just reduce their volume of criminal activity; which means fewer people end up victimized by crime and less work for police, prosecutors, courts and prisons

In general, addressing the “root causes” of crime is a complement, not a substitute, for a well-functioning criminal justice system. This post will be a high-level view of how the safety net interacts with crime in DC and the implications for budget priorities.

Poverty, privation and crime in DC:

Gabe Cohen’s story on juvenile crime in DC is a good introduction to why some youth “crash out” and commit crimes:

Marcelles Queen of “Representation for the Bottom” mentors teens and pointed out the need for both accountability and early interventions:

“I want (them) to understand that the playing is over, that they’re trying to hold you accountable,” and later lamented ““If they intervene way before the point of ‘crashing out,’ then it would never happen,” Queen said. “Every single case (of a child facing criminal charges) you see 100 days missing school, no food in the household. Why does it take something so major to see, oh, we’re failing our kids.””

These anecdotes align with the data. A Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC) study found that problems within the home and school were serious risk factors for future arrests:

While these challenges are statistically-significant risk factors, they aren’t anywhere close to a guarantee that a “high risk” child will engage in criminal activity. Even in the “highest-risk” quartile in the CJCC study only 13% of kids are likely to end up “justice system involved” or arrested. Again, minimizing these risk factors and improving kids’ lives can help prevent them from falling into criminal activity; but the risk factors aren’t a guarantee or excuse for criminal behavior.

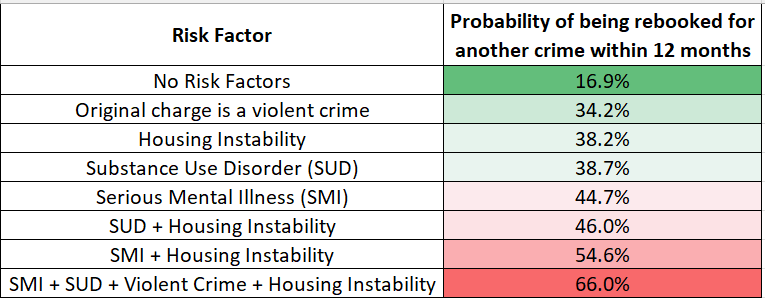

We see a similar pattern with adult criminals in DC. Another CJCC study found that housing instability, substance use disorder (SUD), serious mental illness (SMI) and combinations thereof increased the risk of recidivism (more in this post):

It should be no surprise that unemployed persons are a majority of those arrested and booked at the DC jail:

Of course unemployment and criminal records sometimes reinforce each other. One RAND study found that “More than half of unemployed American men in their 30s have a history of being arrested or convicted of a crime” which can then make it much harder to find a job. This is one way that earlier mistakes can cascade through a person’s life and potentially contribute to more criminal activity.

In DC poverty and employment outcomes are extremely unequal, with implications for which Washingtonians are more likely to end up involved in the criminal justice system. Wards 7 and 8 have both much higher unemployment rates and ~half as many employed workers as DC’s wealthier wards; while being home to 37% of the District’s children. Economic conditions that would be considered an emergency in need of prompt action if they occurred at the District-level are normalized by DC’s political system when it happens in DC’s poorer neighborhoods:

In addition to these poverty and behavioral health risk factors there is a well-documented “age curve” in crime. In 2022 for example the known offenders (36%-39% of this data had an “Unknown” age) were overwhelmingly under age 40. Many people who engage in criminal activity in their youth tend to “age out” of crime though this is not a universal phenomenon:

Because people in poverty, younger people and those with behavioral health needs are at higher risk of criminal activity it makes sense that efforts to help those populations can reduce crime. It’s important to remember that even though these kinds of efforts can’t prevent every crime; any improvement on the margin means fewer victims and less work for the criminal justice system.

How the safety net prevent crime:

Thankfully governments have a number of safety net tools to address poverty and its related social ills that studies show do help lower crime rates:

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) provides funds for lower income families to buy food. In many households receiving SNAP they receive the funds at the beginning of the month and exhaust those benefits in a few weeks; leaving the household very resource-constrained at the end of the month. One paper explored simply how changing when SNAP funds were distributed to families by smoothing out the distribution schedule throughout the month “led to a precipitous drop in crime and theft at grocery stores (17.5% and 20.9%, respectively). The days with the greatest decline were those around the 3rd week of the month.” This kind of intervention works because the underlying crime is motivated by a lack of resources: “Evidence suggests that women are more likely to steal food or other resources after exhausting their benefits. The data shows us that crime increases by 14.2% for women in the fourth week of the month after receiving SNAP benefits.” In this case the government was able to reduce the motivation to steal by forcing better rationing of funds throughout the month. This is an example of how crime that is motivated by material needs can be reduced if those needs are instead met legitimately through safety net programs.

Medicaid covers the cost of health care for low-income Americans and multiple studies have shown that expanding Medicaid decreases crime while shrinking Medicaid increases crime. Because some states implemented the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion while others did not researchers were able to compare how the expansion impacted crime rates: “Medicaid expansion produced a 20-32% negative difference in overall arrests rates in the first three years. We observe the largest negative differences for drug arrests: we find a 25-41% negative difference in drug arrests in the three years following Medicaid expansion, compared to non-expansion counties. We observe a 19-29% negative difference in arrests for violence in the three years after Medicaid expansion, and a decrease in low-level arrests between 24-28% in expansion counties compared to non-expansion counties. Our main results for drug arrests are robust to multiple sensitivity analyses, including a state-level model.” In the other direction, when Tennessee shrunk its Medicaid enrollment it was associated with a statistically significant increase in assaults and thefts. Medicaid covers a variety of services so the causal mechanism isn’t as clear-cut as the SNAP example. Better access to treatment for mental health and substance abuse issues could certainly help some higher-risk repeat offenders avoid recidivism. There’s also the direct financial boost for Medicaid recipients who otherwise would pay much more for healthcare. Both of these channels help stabilize people’s lives and seem to help reduce crime.

Since housing instability is such a huge risk factor for crime it’s no surprise that programs to safely house people can reduce crime. In Denver “People referred to supportive housing experienced eight fewer police contacts and four fewer arrests than those who received usual services in the community. This represents a 34 percent reduction in police contacts and a 40 percent reduction in arrests.” There are so many benefits to stable housing (vs. living on the street) that this program’s impact on crime can come from a number of channels but two key channels are more stable treatment of underlying mental health/substance abuse issues and fewer “public disorder” arrests from altercations in public.

Payments of $1,000 a year from the Alaska Permanent Fund were associated with large decreases in referrals for child neglect and physical abuse. This is a good example of how the stressors of poverty can tip people into criminal behavior (that unlike theft has no possible “economic” motive) and even small amounts of relief can prevent crime. Recall also that child abuse/neglect was itself a risk factor for juveniles getting arrested so this kind of research suggests that helping families can disrupt inter-generational criminal behavior.

A few studies doesn’t mean that every safety net program everywhere reduces crime. But given how some crime is clearly tied to the problems that stem from poverty and behavioral health it makes sense that addressing those problems helps prevent crime. This suggests that even DC’s imperfect social safety net is doing critical work holding back what would be otherwise even higher crime rates. This also implies that the many operational and resourcing problems in our safety net programs mean we don’t get the full potential benefit of these programs.

The dysfunction in DC’s social safety net:

Sadly many well-intentioned programs in DC perform very poorly; especially when it comes to services for the poor. We also see cases where specific points of failure undermine the effectiveness of the entire program. The analogy from the public safety space would be how the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO) declining to prosecute 2/3 of arrests in Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 undermined the crime-fighting benefit of the $565 million that DC spent on the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) that year. We see these kinds of procedural “bottlenecks” throughout DC government services:

DC’s SNAP program “ranked last nationally for timely processing of SNAP applications in Fiscal Year 2022 with a rate of just 42.86% (the second worst performer was Guam at 65.93%)” which means that Washingtonians received their benefits much slower than other Americans. “Less than half of eligible seniors (48%) are enrolled in SNAP” which while a low-crime cohort helps show how DC’s safety net often struggles to reach people.

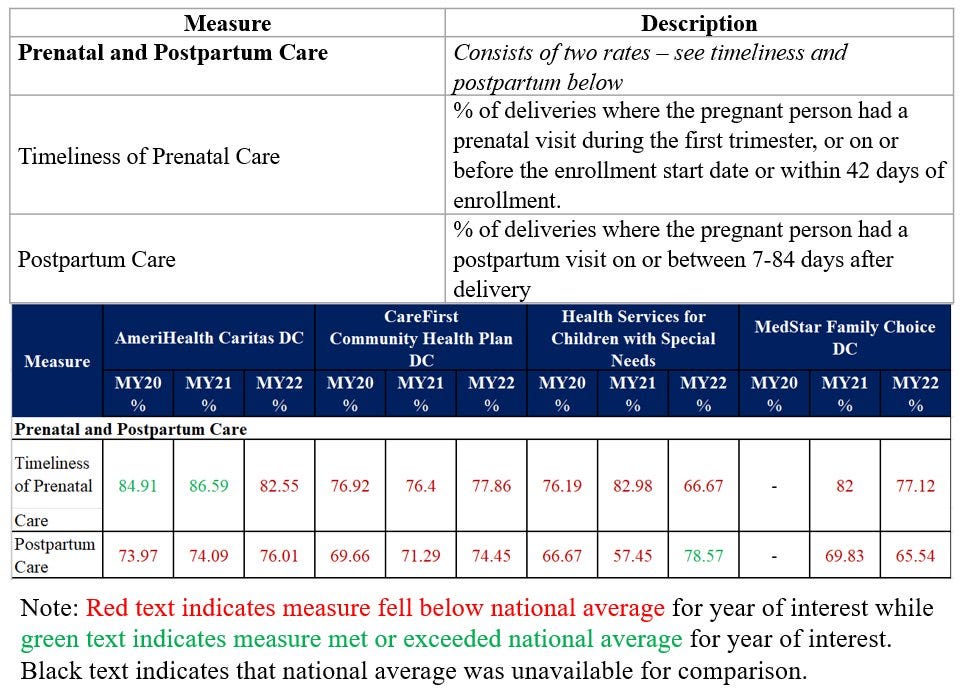

DC’s Medicaid program has similar processing struggles with “43% of pending Medicaid renewal applications (more than 6,900 applications), were pending review for more than 60 days. 27% of renewal applications (more than 4,300), were pending review for more than 90 days” as of October 2023. There are also key performance issues for services like prenatal and postpartum care where most DC Medicaid plans perform worse than the national average and DC “has the fourth highest fetal mortality rate among the jurisdictions that reported data from 2019 to 2021 at 5.38 deaths per 1,000 compared to the national rate of 3.66.”

The DC Housing Authority (DCHA) has long been embroiled in scandal and a “scathing federal audit of the D.C. Housing Authority found that the agency is failing in some of its most basic tasks, from maintaining public housing units in habitable condition to ensuring that every usable unit is actually offered to the thousands of low-income residents who have waited for years for a place to live.” DCHA had “among the lowest public housing occupancy rates in the nation” and despite promises by former Executive Director Brenda Donald to raise the occupancy rate it “fell to about 73 percent by the end of her tenure, even as many thousands of names languished on a frozen waiting list for units.” There are many problems with DCHA but one representative issue is how they signed a $4.35M contract for a “real estate management system” in 2018 but “The software still can’t be used effectively because staffers were never properly trained.”

DC’s housing programs also involve the Department of Human Services (DHS) which helps administer “Permanent Supportive Housing” vouchers for people who are chronically homeless. Here again the processing times are incredibly long; in 2022 “voucher holders faced a nearly nine-month wait for the process to play out, according to data from the DHS. Recent reforms brought the delay down to about 4½ months.” These delays can often be deadly. In 2023, 90 people who were homeless died and 54 of them had been matched to a housing voucher but had not yet been able to move into stable housing.

The problems in DC’s social safety net and programs that serve vulnerable families go beyond these examples. 60% of high schoolers were chronically absent last school year. Young people with court-ordered psychiatric treatment can end up detained for months because of paperwork and access issues. Desperate parents struggle to get their kids help before they commit serious crimes. These issues cut across a number of government agencies and reflect a mix of operational problems and resource constraints. There’s a lot of room for DC to improve how our safety net functions and prevents crime but today the fear is that the safety net is about to be gutted to cover budget deficits.

DC’s deficit and how we pay for local government:

DC’s approved budget for this current fiscal year (FY 2024) spends $19.8 billion:

$10.7 billion is from local revenues like income tax, property tax and sales tax

$5.0 billion is from Federal grants and Medicaid payments

$2.6 billion is from “Enterprise Funds” or “self-sustaining operations for which a fee is charged to external users for goods and services” that are separate from the general fund

$1.5 billion from the remaining categories “Special Purpose Revenue”, “Dedicated Taxes,” “Federal Payments” and private grants/donations

Like most states, DC is required by law to have a balanced budget. This generally means that if revenues decline or expenses increase those “unfavorable” changes have to be offset by either revenue increases or spending cuts elsewhere in the budget. In the next fiscal year (the FY 2025 budget that will go into effect in October 2024) DC is facing multiple budget pressures:

Federal funds are decreasing as COVID-era aid to state and local governments expires. This is Federal law and DC’s local government has no control over this.

Compensation increases for some DC government workers (part of collective bargaining between public employee unions and the DC government) mean that some agencies are facing higher operating costs per employee.

DC’s political leaders have agreed to increased funding for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) to avert service cuts

These pressures outweigh the “favorable” changes from the Chief Financial Officer’s (CFO) forecast that (absent any policy changes) local government revenues would increase by $277 million due to economic and population growth. To further complicate matters there is a dispute between Mayor Bowser, Council Chairman Mendelson and CFO Lee over DC’s reserve funds. The uncertainty around these changes mean that public officials have shared different estimates of how large DC’s “deficit” would be if one carried forward the same tax and spending policies from this current fiscal year; with ranges in media reports from $600 million to $1 billion. Because DC is required by law to have a balanced budget the policy debate is really about how to cover that gap with revenue increases, spending cuts or a mix of both. For comparison, DC spends ~$100 million on “violence prevention” (Safe Passages, Pathways, Violence Interrupters, hospital intervention services etc.) annually and MPD spent $642 million last fiscal year. Even if we eliminated every dollar spent on violence prevention we’d still have a large gap. Given that DC’s social safety net plays a key role in stabilizing families and its functioning impacts crime rates, it’s important that we have a balanced approach to closing this gap. “Gut the safety net to avoid a tax increase on the wealthy” would be wildly unpopular in incredibly Democratic DC but opponents of tax increases have been very successful in framing this debate around their preferred narrative:

They’ve portrayed this $600M-$1B shortfall as being primarily driven by safety net programs like a one-time $39.6M expansion of SNAP benefits

They have framed tax changes as requiring the consensus endorsement of the Tax Revision Commission (TRC) and then successfully delayed any recommendations from the TRC until after this budget cycle

If taken to its logical conclusion this would take revenue increases “off the table” and force a 100% cuts-driven approach for FY 2025

One conservative commission member also argued for “triggers” that would automatically cut taxes if revenues grew. This would make DC’s fiscal policy even more pro-cyclical (which many economists would argue is bad) and is basically an attempt to force a downward ratchet on taxes and spending; taxes would be cut during economic booms and then spending would be cut during recessions.

They have focused concern on tax increases possibly driving out wealthy Washingtonians and businesses rather than on the impact of possible budget cuts

This concern of “high-income flight” makes some sense but an analysis by the Tax Revision Commission found “no evidence in these data that high-income residents left the District in response to the tax changes” that raised taxes on people making $250K and up in 2022.

They focus attention on DC’s income tax, which does have a high marginal tax rate at the highest income brackets, to portray the DC tax code as unfair to the wealthy. They do this while selectively ignoring the other elements of the tax code that cause the wealthiest 5% of Washingtonians to pay a smaller share of their income in taxes than middle class Washingtonians:

The graph above is from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) report which is an incredibly resource on how state tax policies impact different segments of society. This graph helps us understand some key points about DC’s tax code:

Regressive parts of the tax code help those in the top 5% (families making $399K and up) pay a lower effective tax rate than the 55% of families earning between $56K-$399K

Progressive parts of the tax code mean that the lowest income Washingtonians (families earning less than $26K a year) pay much less in taxes. If DC’s tax code was as harsh as Florida’s, poor Washingtonians would pay an extra 8.4% of their income in taxes.

However, “65% of renter households with incomes under $50,000” spent more than half of their income on rent. For the poorest Washingtonians housing costs are 10 times as important as taxes and high housing costs can swamp the boost they receive from DC’s tax code.

From a crime-fighting perspective, we should be far more worried about how the families in the lower part of the income distribution are doing

One part of the tax code that disproportionately helps wealthier Washingtonians are tax expenditures. These are essentially about $2 billion in spending through the tax code but because they aren’t a line item on the “spending” side of the budget they don’t have to be paid for every year and therefore don’t get as much notice. Just over half of DC’s tax expenditures are “Federal conformity” expenditures “which apply U.S. Internal Revenue Code provisions to the D.C. personal and corporate income taxes.” This is quite common among states but it replicates many of the problems of the Federal tax code at a cost to DC local government revenues. Here are some of the larger (by financial impact) and more regressive tax expenditures in DC law:

$283 million in lost revenue from excluding “Employer contributions for medical insurance premiums and medical care” from taxation, which tends to benefit higher-income workers with more generous insurance plans. The report also notes that “Most health economists think the unlimited exclusion for employer-provided health benefits has distorted the markets for both health insurance and health care. Generous health plans encourage subscribers to use health services that are not cost-effective, putting upward pressure on health care costs.”

$116 million in 3 different capital gains exclusions for transferring assets at death, transferring assets as a gift and for the sale of a principal residence. Unsurprisingly any policy that favors capital gains tends to be regressive: “Excluding the capital gains on the sale of principal residences from tax primarily benefits middle- and upper-income taxpayers.”

$74 million for the charitable contribution deduction. While such donations are often laudable, this tax provision is very regressive. Claimants with “federal AGI of $200,000 or more comprised only 35 percent of claimants but accounted for 71 percent of the total amount deducted.”

$53 million from a tax deduction for “Mortgage interest on owner-occupied residences.” This deduction tends to benefit higher-earners with “Taxpayers with federal adjusted gross income of $100,000 or more comprised about 72 percent of the beneficiaries and claimed an estimated 81 percent of the total amount deducted.” The report also notes that instead of encouraging more homeownership it may just raise housing prices: “The value of the U.S. deduction may be at least partly capitalized into higher prices at the middle and upper end of the market”

To be clear, DC is very unlikely to make any wholesale changes to these tax expenditures. But we should ask if replicating the least-effective parts of the Federal tax code are the best uses of our marginal dollars. These tax expenditures help explain why the wealthiest Washingtonians pay a lower effective local tax rate than middle class families.

In addition to this menu of tax expenditures we also have analysis from the Tax Revision Commission. While their “Chairman’s Mark” insisted that their recommendations be taken as a revenue-neutral package there’s nothing stopping policymakers from using these revenue estimates and analyses; especially since the Commission failed to deliver final recommendations in time for this budget cycle. According to the Washington City Paper, much of the fighting within the Commission centered on a “business activity tax (BAT)” that would raise ~$275 million. The Commission appears to have separately considered but delayed a “move to system of split-rate "land value" taxation for commercial properties when values stabilize.” Land Value Taxes tend to be less regressive than traditional property taxes and encourage more economic development. DC’s current property tax approach tilts the tax burden towards apartments (which gets passed on as higher rents for tenants) and provides lower taxes for property owners with large yards (a population which skews wealthier). DC also recently enacted a tax cut for real estate transactions that has a cost of over $90 million a year. The fact that the regressive aspects of DC’s tax code get so little public attention is one of the biggest messaging victories of DC’s business community and their allies. Normally this aspect of tax policy doesn’t have much to do with crime; but if we end up “forced” into gutting public safety and social safety net agencies because of these regressive choices it could endanger DC’s recovery from the Spring-Summer 2023 crime spike.

The same budget cycle where the message is DC needs to cut services that primarily benefit lower and middle-income Washingtonians is also one where supposedly we need to offer “big tax breaks for developers” downtown. It’s unclear how much the Mayor intends to fund these “investments” but it’s a stark contrast to how the rest of the budget is being messaged:

The poll at the beginning of this post is part of a consistent pattern that Washingtonians want to prevent and deter crime. The public’s intuition that assisting vulnerable people can help prevent crime aligns with what we see in research. We know that DC’s safety net programs have a lot of problems; some operational and some financial. Budget cuts need to be carefully targeted, paired with real plans (and transparency) to improve operations and be balanced with a critical eye towards fixing the regressive parts of DC’s tax code.

Everyone in DC, especially people in government and journalism (but really everyone) should read this newsletter. Seriously the best local reporting I have seen. Thank you.