"We know what we need to do, but it just hasn't really happened"

Fixing DC's broken gun violence approach

This post’s title quote is from David Muhammad, the Executive Director of the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (NICJR), in an interview with NBC4’s Ted Oberg about DC’s violence prevention efforts. Mr. Muhammad is absolutely correct and this week his organization released an updated Gun Violence Problem Analysis that shows DC’s system is repeatedly failing to deter the small number of people (200-500) that are driving the majority of DC’s homicides and shootings. The key damning fact from the analysis is that 83% of homicide suspects have been arrested for other offenses before the murder and “most victims and suspects with prior criminal offenses had been arrested about 10 times for about 12 different offenses by the time of the homicide.” DC’s prosecutors, courts, supervision agencies and violence prevention programs are getting chance after chance to incapacitate or rehabilitate these suspects and their collective failure is driving DC’s homicide rate.

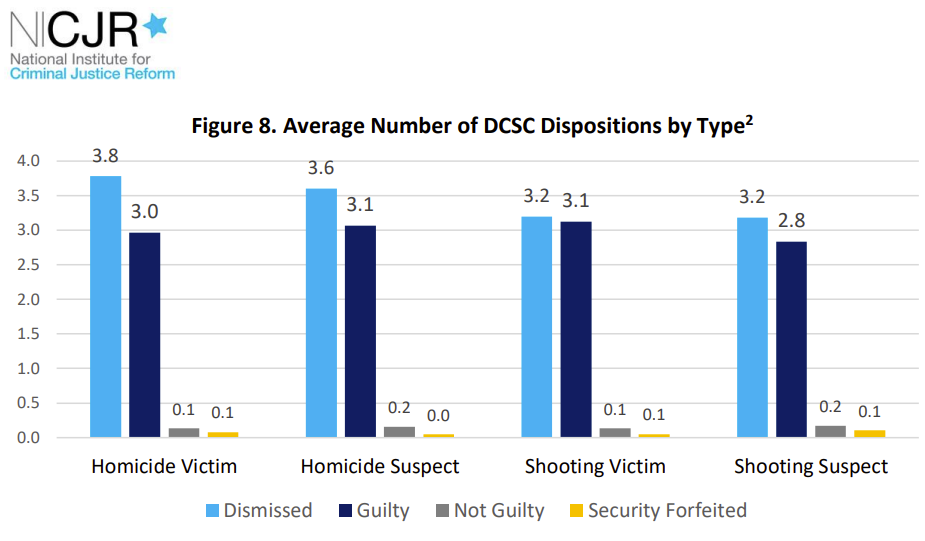

The Gun Violence Problem Analysis tracks homicide suspects/victims as well as non-fatal shooting suspects/victims. Broadly speaking the past criminal history and demographics are very similar between the homicide and non-fatal shooting populations:

Homicide suspects and victims overwhelmingly have extensive involvement with the criminal justice system before the murder:

83% of homicide suspects have been arrested before, with a large share of them having active (at the time of the murder) or prior supervision with the Pretrial Services Agency (PSA), the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA), were previously booked at the DC jail (DOC) or spent time in federal prison (BOP) for other offenses

The most common prior offenses are drug charges but many homicide suspects also have previous violent crime and gun offenses (highlighted in the red boxes below)

The high rate of drug offenses makes sense since many homicide suspects and victims are parts of gangs/crews and “Many groups/gangs in the District of Columbia are heavily engaged in narcotics sales.” The report identifies “at least 84” criminal organizations (gangs, crews etc.) that were represented among DC’s homicide suspects or victims. These groups violently compete for control of the drug trade in their neighborhoods and often get into petty disputes that turn deadly:

“Among interviewees, there was nearly unanimous agreement on the primary driver of gun violence in the District. There is a deadly mix of group/crew/gang members making music videos taunting or disrespecting their rivals that are posted on social media, and those videos spark or further inflame neighborhood conflicts that escalate into shootings. And while the music videos were identified as the primary issue, other comments and pictures posted to social media by group members also lead to shootings.

Officers and Violence Interrupters also identified other leading causes of shootings, including drug sales and drug use; robberies; personal disputes like fighting over a young woman, although that often includes guys who are also in groups/crews; and the increased availability of firearms, including ghost guns.”

While specific shootings are often sparked by social media insults and personal disputes; the underlying problem is these groups of armed men with longstanding grievances against each other and no fear of consequences for their actions. “Taken together, officers, and surprisingly even many Violence Interrupters, described a feeling of impunity among many people on the streets that may be encouraging criminal behavior.” It’s worth diving into why these offenders have this “feeling of impunity” despite having an average of ten previous adult arrests (with the possibility for even more uncounted juvenile arrests).

For regular readers it will not be surprising that this sense of impunity stems largely from a lack of prosecution. The United States Attorney’s Office (USAO) has one of the lowest prosecution rates of any big city prosecutor in America and it’s no different for this population of highest-risk homicide suspects:

The average of 10 arrests for 12 offenses for each suspect only results in ~6.9 charged cases

Of those 6.9 cases the USAO ends up dropping 3.6 or 52% of them (“dismissed” in the chart). This can be the result of the USAO deciding the case was too weak, a plea bargain, a loss on the suppression of evidence, “prosecutor discretion” or other factors.

While the average homicide suspect has 3.1 prior convictions, only 54% have any prior felony conviction. This suggests that a lot of these convictions are for misdemeanors. In other reports we’ve seen this occur from plea bargains allowing the suspect to plead guilty only to a misdemeanor or the USAO downgrading the initial charges from a felony to a misdemeanor.

Despite all of these prior arrests, only 40% of homicide suspects ever spent any time in prison before the murder. This is directly because of the USAO’s prosecution “filter” declining, dropping and pleading down charges far more than other big city prosecutors.

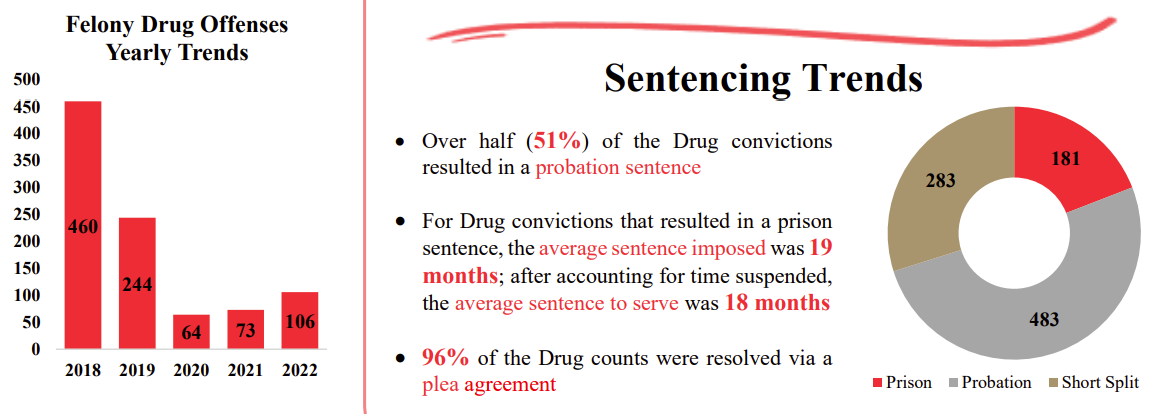

While United States Attorney Graves has said his office will “go after the individuals that we know to be driving violence” we’ve actually seen some of the sharpest decreases in prosecution in exactly the kind of drug, firearm and violent offenses that these gangs/crews engage in. Drug arrests and prosecutions in DC have been decreasing for years and then essentially collapsed when DC’s crime lab lost accreditation in April 2021. Almost no cases moved forward, even when police caught suspects with large quantities of drugs, because police and prosecutors couldn’t test the evidence to prove the cases in court. As a result, convictions for felony drug offenses plunged:

It wasn’t until the USAO got in trouble for their record-low Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 prosecution rate and the USAO blamed the crime lab in their media responses that the USAO and Bowser administration took any steps to increase evidence testing capacity to fix this problem. Given how involved gangs/crews are in both shootings and the drug trade; it’s very likely that the collapse in drug prosecutions increased both the number of would-be shooters were on the street and their feeling of “impunity.” The theory is that the pre-COVID rate of drug prosecutions (when the USAO was charging more cases overall and the crime lab was functional) helped to incapacitate some of DC’s highest-risk shooters/victims and therefore helped keep the homicide rate lower than today. In addition we also saw the USAO’s prosecution rate for felonies in general fall from 83% in FY 2017 to just 47% in FY 2022. For Washingtonians looking for an answer to "why did murder rise in DC but fall in other cities?" this is a uniquely DC problem (no other city has such a low prosecution rate AND a dysfunctional crime lab) and it’s directly related to the specific (small) population driving the homicide rate. Despite Mayor Bowser’s meticulously groomed “tough on crime” image; her administration’s mismanagement of the crime lab and ignoring analyst warnings about decreasing USAO prosecutions directly fueled the increase in gang-related gun violence that we’re dealing with today.

There are reasons for cautious optimism that DC will do a better job incapacitating and deterring this highest-risk population in the near-term:

USAO prosecution rates are still lower than other cities but they are higher than the record-low rates in FY 2022. Media and political pressure seems to have forced some changes though there are still serious problems.

The Department of Justice is deploying more agents, analysts and prosecutors to fight violent crime in DC and made a big media splash in doing so. This indicates some political investment by the Biden administration in seeing “crime falls in DC” stories become a reality. The stated focus of these new resources is exactly on these highest-risk “drivers of violence” and the announcement is hopefully an admission that the previous resourcing and prosecutorial approach wasn’t working.

DC’s crime lab recently regained accreditation for its Forensic Chemistry Unit (FCU) and Forensic Biology Unit (FBU) which will allow it to resume drug and DNA testing. This should help to solve more cases and convince the USAO to press charges. Unfortunately there are still massive backlogs of untested evidence and even under optimistic scenarios it may take half a year to catch up on the DNA backlog:

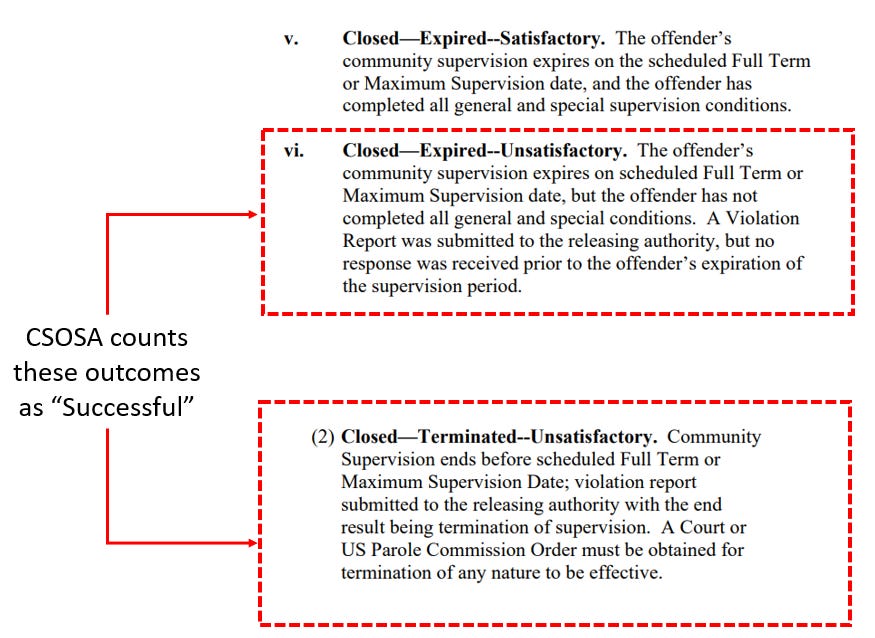

As we try to restore deterrence and incapacitate these highest-risk suspects we also need to do a better job of rehabilitating people before they pull the trigger. This responsibility is fragmented across Federal agencies like CSOSA and “about 100 different programs” across the DC government. CSOSA’s operations include both pretrial supervision (PSA) and post-conviction supervision (CSP) like probation, parole and supervised release. Remember that a large majority of homicide suspects are either under active CSOSA/PSA supervision at the time of the murder or had been previously under CSOSA/PSA supervision. CSOSA is supposed to be trying to address underlying issues that may contribute to recidivism among its supervised population but the follow through is often lacking. Both PSA and CSP have struggled to get people into treatment for substance use disorders and they don’t tend to report out any data on how they are trying to address their charges’ social needs like housing and employment. Like the USAO, CSOSA isn’t accountable to DC’s elected government and they very rarely share data with the public. They haven’t released Fiscal Year 2023 data yet but in FY 2022 they had the lowest rate of “Successful” completions in at least 4 years:

Even that low 64% “Successful” statistic is misleading. CSOSA’s definition of success includes cases where an offender does not complete their conditions:

Release conditions vary but in many cases they are core rehabilitative steps like “seek mental health treatment” or seeking a job or education. We don’t have data from CSOSA on what kinds of conditions are/are not being met by their population so we don’t know where the DC government or private groups could/should be trying to fill gaps. It’s also notable that CSOSA is primarily evaluated on what % of their supervised population are re-arrested while under supervision. This is a good metric but the fact that there’s no accountability for what happens after an offender leaves CSOSA supervision means there’s less incentive for efforts at true rehabilitation. Post-conviction supervision alone has a budget of over $200M (about double even the most-expansive estimate for DC’s local “violence prevention” efforts) and yet we have very little transparency into what they are doing. Hopefully local media and policymakers (especially the Judiciary and Public Safety Committee of the DC Council) can dig more into CSOSA’s operations.

In addition to CSOSA we have the bewildering array of “about 100 different programs” that ostensibly do “violence prevention” in the District government. Here’s how the Bowser administration portrayed this part of the “ecosystem” in a presentation to ANCs:

NICJR Executive Director David Muhammad described the mismatch between the variety of resources available and DC’s violent crime outcomes: “D.C. is particularly challenging given there's a good amount of resources. There's also a lot of talented people,” “They're just not coming together. They’re just not coordinated.”

One key point is that many of these programs are not focused on the 200-500 highest-risk people driving gun violence in DC. Things like Truancy Reduction, Safe Passage and DC SchoolConnect have value in helping youth but aren’t really related to the adult gangs/crews that drive most gun violence in DC. While the highest-risk suspects may encounter some of these other programs, the most relevant DC programs for gun violence prevention are:

Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement (ONSE) Violence Intervention (VI)

Office of the Attorney General’s (OAG) Cure The Streets program

People of Promise

Pathways Program

In DC’s two parallel violence intervention programs (ONSE VI and Cure The Streets) grantees are assigned to specific gangs/crews/geographic areas and are tasked with trying to mediate feuds, broker truces and steering gang members towards a better path. Given the research consensus that petty feuds between gangs/crews are a huge driver of gun violence it does make sense to try to intervene and prevent shootings from escalating into a retaliatory cycle. In this sense violence intervention can help reduce violence and make things easier for law enforcement without replacing the need for law enforcement. However when we move from theory to practice we get very uneven implementation across the District:

The Cure The Streets areas actually saw a decrease in homicides in 2023 while violence soared in the rest of the District

On both gun homicides and gun ADWs the ONSE areas did worse than the Cure The Streets areas, but still less-bad than the parts of the District with no violence intervention programs

There is a pretty large political consensus that it doesn’t make operational sense for DC to have 2 parallel violence intervention programs and there is a lot of pressure to merge ONSE and Cure The Streets. The danger is if Cure The Streets is merged into ONSE and begins to show worse outcomes like ONSE. Councilmember Pinto’s committee noted “the Committee has heard that OAG’s Cure the Streets program has been more successful than ONSE’s VII program at least in part because of a greater concentration of resources in a smaller area.” The 2023 crime data should raise further concerns about giving more authority to ONSE until they can show improved performance relative to Cure The Streets.

As a department, ONSE has had a series of misfortune and missteps. ONSE’s former Director tragically passed away in May 2023. Mayor Bowser has still not nominated a permanent replacement and it appears that Interim Director Kwelli Sneed has been in the role far longer than DC law allows for interim agency heads. The most recent “impact” data on the ONSE website is from November 2021 and ONSE was one of many DC agencies with a nonsensical performance plan. The Pathways Program doesn’t share ongoing data but when they were forced to report outcomes during performance oversight we saw that very few program graduates were actually securing unsubsidized jobs:

ONSE also got a black eye from the disastrous rollout of the People of Promise program. The intent of People of Promise was to reach the 200-500 highest-risk people identified by the first Gun Violence Problem Analysis and get them “the services and resources People of Promise need to overcome their hurt and trauma and stabilize their lives”. The Washington Post summed up the initial phase of the program this way: “The city has yet to reach about half of those on its “People of Promise” list, and a top official graded the program as a C-plus.”

DC needs better performance (and more transparency) out of ONSE if we’re serious about tackling gun violence but their work needs to be supported by vigorous prosecution. DC’s political class has created a false dichotomy where efforts at prevention and enforcement are seen as an either/or choice. In reality, proven effective crime-fighting approaches like Focused Deterrence use both “carrots” (outreach and rehabilitative supports) and “sticks” (vigorous prosecution) to reduce crime.

This is now the second time that DC has paid for an excellent analysis of our gun violence problem. Unfortunately our crime-fighting ecosystem completely failed to competently act on the findings of the first analysis and almost 500 people have been killed in DC since its release. We cannot repeat those mistakes.

Researching and writing these posts is a tremendous public service. Thank you.

This is another great article with so much useful information. I have told all of my friends about this resource (and both of them really enjoyed it. I kid, i have 3 friends, actually). Anyway, I'm really interested in the last half of this report. The violence prevention and rehabilitation programs seem like they are the critical piece. Assume, for the sake of argument, that the renewed focus by the city and the feds pans out, and the arrests, prosecution, and incarceration rates all improve. What happens then? How do these violence prevention programs and intervention programs work? Or, rather, how are they intended to work? (The stats at the end of this post for the programs DC has so far aren't promising.) What are other cities, states, and countries doing to get these people out of the cycle of crime and violence, and how can we implement those tactics? Joe Friday's analysis of the crime and prosecution stats is so clear and useful, I would love to see him focus on some prevention prescriptions. Keep it up!