Ideally we prevent crime before it happens. In addition to deterring criminals with effective policing and prosecutions; there are many ways the government, community groups and individuals can help prevent crime. Here are 3 key levers:

Keep kids safe: Preventable or addressable family, health and educational issues can make a DC child 3 times more likely to be arrested. As many as 20% of kids with the most challenging combinations of risk factors end up in the juvenile justice system.

Avoid recidivism: Addressable mental illness, substance use and housing challenges can make “returning citizens” 21-59% more likely to return to prison

Interrupt violence: Successful DC groups have helped reduce shootings by 14-42% in their targeted neighborhoods but other areas are struggling

DC is fortunate that we have some excellent researchers at the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC). They have produced many reports that identify statistically significant and meaningful drivers of crime based on DC’s specific population and circumstances. These give us a solid understanding of where to focus long-term prevention efforts. In October 2022, CJCC produced a robust analysis of 2,981 demographically representative children enrolled in DCPS/DCPCS schools. The report quantified the impact of certain risk factors on a child’s likelihood of being arrested. While “being arrested” doesn’t perfectly correlate with “engaged in crime” it’s still a valuable data point in identifying what puts kids at higher risk and what we can try to prevent:

Several risk factors (like being removed from home or experiencing abuse) were statistically significant and raise a child’s likelihood of eventually being arrested by anywhere from 1.3-3.1 times more than average. When a child combines multiple risk factors their risk of being arrested can be as high as 20%.

Notably, the vast majority (87%) of kids in even the highest-risk quarter of students do not get arrested (and this study was mostly before the COVID-era drop in arrest rates). Even kids with the worst circumstances are not “predestined” to engage in crime and any crude stereotyping of these kids as “criminals” would have 6 times as many “false positives” as “true positives.”

Many of these risk factors are situations where there is an administrative record that stands in for larger family, health or educational issues. The acts of CFSA removing a child from home or DCPS holding a child back a grade are almost certainly not the causal driver of future arrests. It’s more important to prevent more kids from falling into these kinds of situations in the first place. The many parents, relatives, neighbors, teachers, social workers and clergy that try and help kids succeed are both doing good work and shrinking the recruitment pool for criminal groups. It sounds cheesy but this data shows that doing good by our kids is also an anti-crime measure.

The latter half of CJCC’s youth arrest report covers best practices and which DC-specific programs are trying to address these risk factors. We have government programs for almost all of these interventions (which is good!) but the key question is how well are they functioning? For example, we’ve seen increased funding for housing vouchers get partially tied up by a lack of administrative capacity. Our summer youth employment program is well-regarded (and this kind of work does prevent crime) but what happens to the ~6K young people that applied but weren’t eligible? As always, oversight is key.

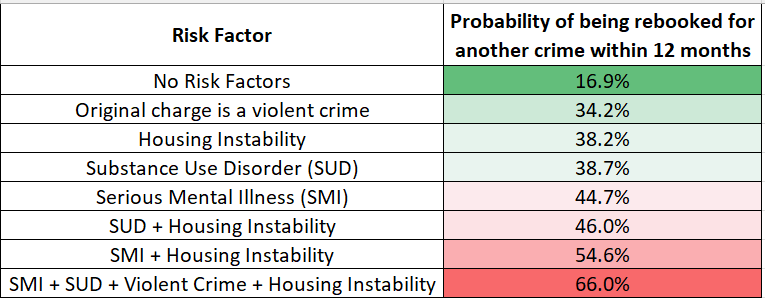

Another way to prevent crime is to ensure that people don’t fall back into crime when they’re released from jail/prison; since a significant share of crimes are committed by this group. This population of “returning citizens”, who were “criminals” at one point, are a lot less politically sympathetic than kids. However, setting them on the right path can reduce crime. Again, CJCC has a well-done study looking at 16,302 individuals that were released back into the DC community after incarceration between 2005-2019. They identified 4 key risk factors for DC’s returning citizens being “rebooked” by the Department of Corrections (DOC) for a subsequent crime:

Pre-incarceration homelessness, serious mental illness, substance use disorders and being initially booked for a violent crime all had statistically significant increases on the probability of a released individual being rebooked by DOC within 12 months of release.

CJCC was only able to collect this data on the person’s status when they were originally incarcerated. As a result, the report likely understated the impact of these (still significant) variables because undoubtedly some people would become homeless or develop mental illness/substance use disorders due to being incarcerated.

43% of released individuals ended up being rebooked. While this is very high in absolute terms, it’s pretty comparable to national averages for recidivism.

The risk factors are multiplicative so people with more than one are at higher risk:

While “counseling for criminals” is often derided as a “weak” policy; so long as we’re releasing people from prison we have a crime-reducing self-interest in treating their mental illness, substance use and even helping them secure housing. Many voters understandably dislike the idea of criminals receiving any “special benefits.” And it is someone’s choice to re-offend; these are risk factors, not justifications. But this robust, DC-specific data clearly confirms what common sense dictates: It’s really hard for people to change their ways and without help, a lot of former criminals won’t. Separate from how long sentences should be; when we do release people we should try and avoid recidivism and mental illness, substance use and housing are obvious, data-driven places to focus. DC has programs to help but implementation is key.

More directly, there are ways to prevent some specific violent crimes. The concept of Violence Interrupters (VI) has been much debated and DC’s 2 programs and 9 different grantees were the subject of mixed reviews by DC’s Auditor. VIs try to reduce armed conflict between criminal groups/gangs/crews by building trusted relationships with group members, defusing tensions and (critically) arguing for meditation instead of retaliation when inter-group violence does occur. This approach is incredibly difficult to scale because it’s built on inter-personal relationships; success in one neighborhood means very little when expanding to another one. So it should be no surprise that VI outcomes vary a lot depending on the neighborhood and which organization is doing the VI work.

Of the 2 VI programs, only the Attorney General’s Cure the Streets program seems to maintain publicly-available updated data on its impact. The Mayor’s VI program website and oversight responses still refer to data from 2021 as of this time.

Cure the Streets measures the # of assault with a deadly weapon (ADW) with a gun and homicide with a gun as their outcome metrics for the areas that each grantee is assigned to. This is reasonable as these are the crimes they are specifically aiming to impact. The data is organized by fiscal year (FY).

Because the program rolled out to different areas in different years, I compared each area’s average number of combined “shootings” (both ADW + Homicide) in the 2 fiscal years before the program started to the average after the program was implemented. For FY 2023 they have 5 months of data (October-February) so I calculated an annualized projection; including a seasonality adjustment since shootings are usually higher in the summer (i.e. a pessimistic projection).

I also compared how each area did relative to DC as a whole. This allows us to somewhat control for the influence of District-wide rises and falls in gun violence and isolate any local impact of the program. This isn’t a controlled study so we can’t attribute all of the good or bad results in an area to Cure the Streets.

2 of the 5 grantees in Cure the Streets seem to have pretty good results, 2 other grantees have mixed results and 1 showed only negative results.

InnerCity Collaborative seems to be doing a good job in Brightwood Park/Petworth. Shootings are down 42% in FY 2023 so far.

The Alliance of Concerned Men (ACM) has helped reduce shootings 24% in Washington Highlands since 2019 and after they took over the Marshall Heights area in FY 2023 shootings have also gone down there.

Father Factor has shown good results (-14% reduction) in the Historic Anacostia/Fairlawn area and had mixed results (a decrease in shootings that was less than the District-wide decrease) in Sursum Code/Ivy City. Unfortunately they’ve had negative results in Bellevue.

The National Association for the Advancement of Returning Citizens (NAARC) had pretty negative results through FY 2022 in their 3 areas. However, they’ve had very low numbers of shootings in FY 2023 so far and it’s unclear what is driving that (welcome) change.

Women in H.E.E.L.S. has had negative results so far in Congress Heights.

If we compare the pre and post rollout average # of shootings across all areas we do see a 6% absolute reduction in shootings. If we compare each area’s performance relative to DC’s overall trend the average reduction is 9.2%. But the reduction overwhelmingly comes from the 4 “Positive” areas:

4 “Positive” Areas: 28% absolute reduction, 29% relative reduction

6 “Mixed” or “Negative Areas: 12% absolute increase, 3.8% relative reduction (some of these areas “increased less” than DC’s overall trend)

This analysis really underscores how personalized this intervention is. It reinforces the fact that with gun violence we’re talking about a very small number of people (about 500 people or 0.07% of Washingtonians) and how to reach each of them varies. That said, I sincerely hope that these grantees are sharing best practices as they navigate this incredibly difficult mission. This is certainly evidence to continue trying to scale and spread the success we seem to have in the 4 positive areas. At $9.7M, Cure the Streets’ cost is equivalent to ~2% of MPD’s budget so it seem to be worth trying.

With DC about to begin a tough budget cycle it’s not likely that we’ll see many large new public investments in these kinds of crime prevention efforts this year. Hopefully, the Council and Mayor will consider these risk factors for crime and recidivism when conducting oversight and setting funding for FY 2024. There are a lot of programs (housing, education, behavioral health etc.) aimed at these crime prevention levers and ensuring they work as intended is a key responsibility.

If you take nothing else from this post I hope you remember that we as individuals are not powerless in this fight. Most of these risk factors for kids and returning citizens are things people and groups can mitigate at a small scale. People who mentor, volunteer, sponsor, employ and otherwise help are doing good and fighting crime in the long run. It’s really hard work but our community’s data shows that it makes an impact.