Like other key parts of the local criminal justice system; DC doesn’t control the agencies that oversee defendants before trials or people on probation/parole/release. This critical function is run by the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA) for the District of Columbia, a Federal agency. This agency generally attracts little attention from Washingtonians. But with the tragic murder of Christy Bautista, allegedly by a suspect who had been released pending sentencing for another crime, it’s worth a look at this agency. In their most recent annual report to Congress they dropped the concerning statistic that persons on parole/probation/release had a 20% higher rearrest rate for new charges in Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 than in FY 2021.

CSOSA is divided into two parts:

The Pretrial Services Agency (PSA), supervises “defendants on pretrial release” and critically act as the experts in advising the court on which defendants to release or hold in the DC jail.

The Community Supervision Program (CSP) supervises “adult offenders on probation, parole and supervised release” i.e. after the case has been resolved

The PSA role is important because it takes cases a long time to process through the courts (and even longer post-COVID). Even with lower arrest rates by MPD and lower charging rates by the USAO, the PSA oversaw 15,353 people in FY 2022 or an average of 8,396 per day. That population is equivalent to ~2% of DC’s total population but note that PSA also oversees non-DC residents who are charged with crimes in DC. One reason this population is relatively large is because the Courts have slowed down. The DC Superior Court has “10 vacancies and only three nominees awaiting congressional approval” and as a result PSA has to manage people for a longer period of time: “Prior to the pandemic, defendants remained under supervision for an average of 92 days During FY 2022, defendants remained under supervision for an average of 134 days.” One concern is that this increased PSA caseload means that each Pretrial Service Officer (PSO) is now overseeing 94 defendants under “general supervision”, up from 74 pre-COVID.

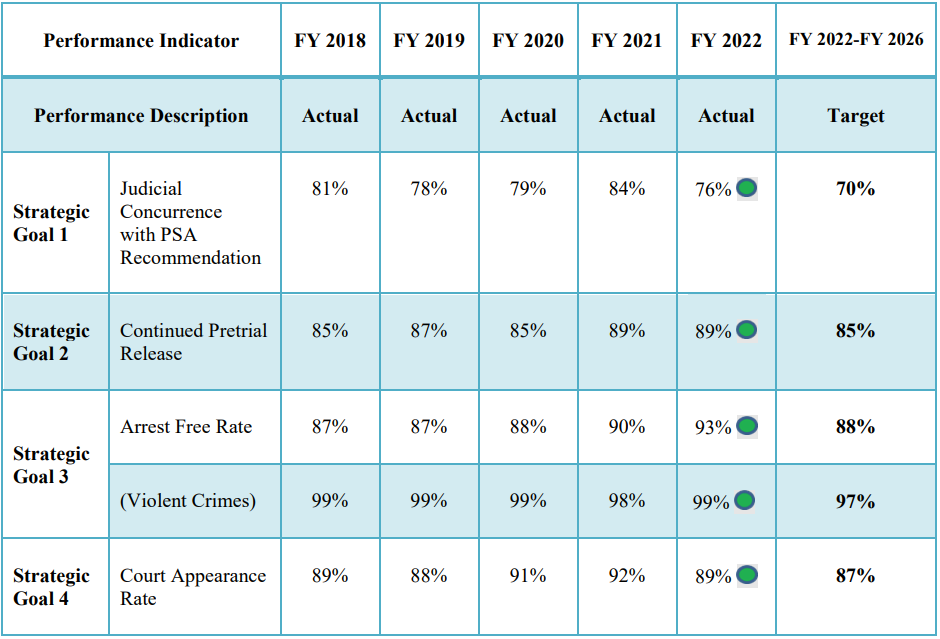

The PSA has 4 major strategic goals, as shown in the table below. We’ll explore each of these goals and their associated performance metrics below:

Strategic Goal 1 Judicial Concurrence with PSA Recommendation

When someone is arrested and charged, PSA conducts a risk assessment on each “arrestee’s demographic information, criminal history, drug use and/or mental health information” when recommending to the court if the arrestee should be released under PSA supervision while their case is processed by the court. However, the final decision is up to the judge and is also influenced by the arguments the defense and USAO bring to bear. In FY 2022 DC courts agreed with PSA’s recommendations 76% of the time, down 8% from FY 2021 (which was heavily influenced by COVID). 76% is “above target” but the target rate of 70% here is lower than any recent year so it’s not a very ambitious goal. The report does not break down how the court disagreed with the PSA’s recommendations. We don’t know if this change represents judges being more strict or more lenient in releasing defendants pre-trial than PSA recommends and this would be a great question for legislators and journalists to investigate.

Based on PSA’s reporting we can get a peek at how “risky” defendants are according to PSA’s risk-assessment methodology. They don’t report risk scores but they do split out if defendants are initially released, subsequently released or detained throughout their case. Since the courts agree with PSA’s recommendations the vast majority of the time we can infer that # of defendants that are detained throughout their case corresponds with the # of “highest risk” defendants, those that were detained and then subsequently released are “medium risk” and those that are initially released are the “low risk”:

This data is for cases filed in that fiscal year (a separate PSA report) so it’s lower than the total number that PSA sees in a year (since some cases carry over). The huge reduction in Low Risk defendants masks a significant reduction in the number of Medium Risk defendants and a relatively stable trend in the Highest Risk population:

This PSA data partially supports the USAO’s claim that even though prosecutions have decreased that they are still focusing on more-serious crimes. However, PSA risk assessments don’t perfectly correspond to the seriousness of the crime and both the Highest and Medium Risk populations were smaller in FY 2022 than pre-COVID.

PSA Strategic Goal 2 Continued Pretrial Release

PSA’s goals try to balance having as many persons be released pretrial with public safety. Pretrial release is much less expensive than pretrial detention and since defendants are innocent until proven guilty there are strong Constitutional reasons for them to promote safe pretrial release. 89% of defendants are released pretrial and this ratio has been pretty consistent, even as the overall pool of defendants has gotten smaller and riskier.

PSA Strategic Goal 3 Minimize Rearrest

The public obviously has a strong interest in seeing that defendants do not commit further crimes while on pretrial release. By PSA’s own metrics they seem to be doing a pretty good job, with only 7% of defendants being rearrested for any charge and only 1% being rearrested for a violent crime. However, failures like what seems to have occurred with Christy Bautista’s murder need to be investigated; both to identify gaps and to reassure the public that the government is taking the problem seriously.

PSA Strategic Goal 4 Court Appearance Rate

Beyond simply not committing further crimes, we also need defendants on pretrial release to show up to court rather than absconding. In FY 2022 PSA had an 89% “court appearance rate”, which is down 3% from FY 2022 but in line with the pre-COVID trend. Again PSA seems to have a very low target of only 87%. In this case, 89% is the vast majority of defendants (good) but it’s unclear why the goal shouldn’t be something much closer to 100%. I shared on Twitter an example I found while auditing some FY 2023 cases where a defendant was non-compliant with their release conditions 4 times before absconding. So between the 11% non-appearance rate and these head-scratching anecdotes this seems like another area for further investigation.

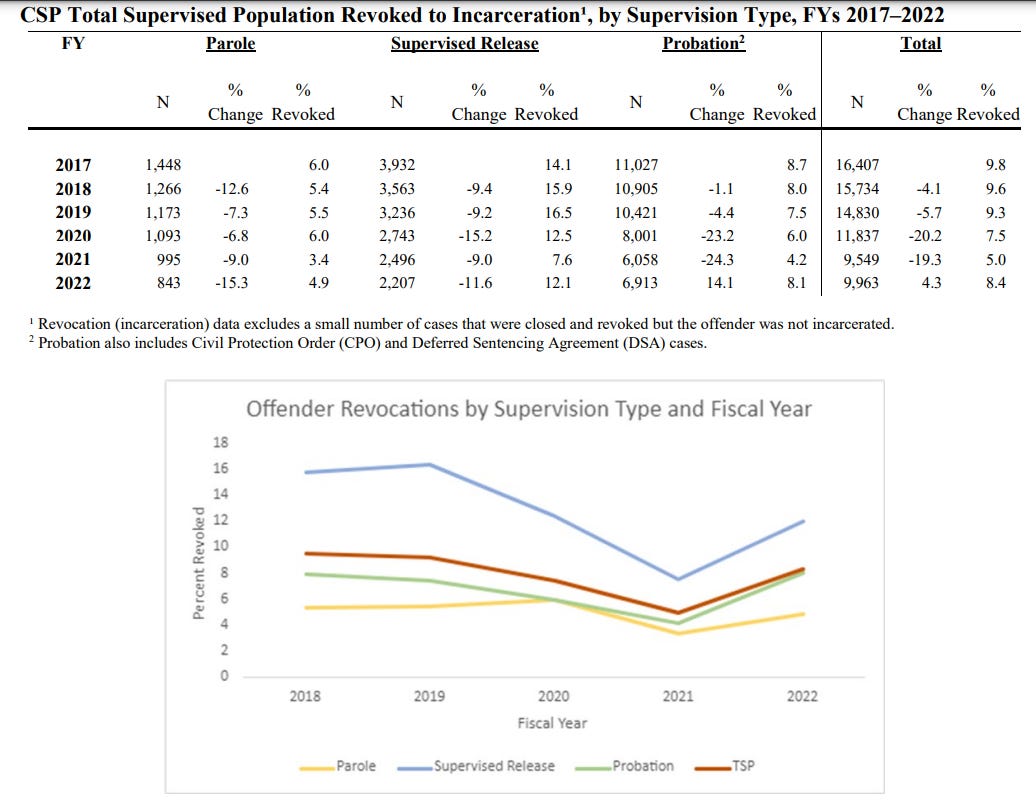

Moving from the pre-trial side of CSOSA we’ll now look at the Community Supervision Program (CSP) who handles folks after their case has resulted in probation, parole or supervised release. In FY 2022 they oversaw “6,700 offenders on any given day and 9,963 different offenders over the course of the year.” This population saw a large 20% increase in their rearrest rate from FY 2021 to FY 2022. Like the PSA, the CSP is overseeing a smaller but higher risk population than pre-COVID: “Based on the results of CSP’s proprietary offender risk and needs screening tool, the Auto Screener, approximately 55 percent of the September 30, 2022 assessed offender population was supervised by CSP at the highest risk levels. This represents an increase from September 2019 when 48 percent of the assessed supervision population was supervised at the highest risk levels.” Unlike the PSA, the CSP is monitoring these individuals for very long times:

I agree with CSP highlighting the challenges of the offender population and it tracks with many of the risk factors for recidivism we covered in this post. CSP tracks what % of persons have their status revoked and are sent back to incarceration. On this metric, FY 2022 was in line with the pre-COVID trend:

In terms of staffing, the CSP’s caseload ratios are below pre-COVID (with the caveat that the supervised pool of offenders appears to be higher risk):

Interestingly, while CSP claims that 2,120 high risk offenders are in the “Maximum” supervision category, only 490 offenders are subject to GPS monitoring. That’s only 23% of the highest-risk population and is something I hope gets more attention, especially as CSP’s rearrest rate rose from 13.3% in FY 2021 to 33.9% in FY 2022. GPS monitoring isn’t perfect but it seems like it may be under-utilized here.

CSP monitors drug use since that does correlate with recidivism (even beyond drug crimes) and about 43% of the subset of offenders that were tested had at least 1 positive test result in FY 2022. That is up 8% from FY 2021 but below pre-COVID. The types of drugs used are shown below with FY 2022 showing large increases in Cocaine and Opiates:

The PSA and CSP are incredibly important parts of DC’s criminal justice system that seem to get very little attention. Hopefully District and Federal leaders can work together to address some of the challenges we’re seeing. I sincerely hope that the Mayor’s upcoming public safety plan addresses the large 20% increase in rearrests that we’re seeing in the CSP population and how the District will work with these Federal agencies to deal with that trend. With that in mind, here are some questions for leaders who want to look into this:

When judges disagree with PSA’s recommendations on pretrial release are the outcomes (showing up in court and not being rearrested) generally better or worse? Is there significant variation by judge?

How is PSA handling non-compliance by defendants on release and how effective are their graduated sanctions at driving compliance?

What caused the 20% increase in rearrest rates by the CSP population?

What is the District government doing to prevent recidivism by this population? What is it planning to do differently in light of this large increase in recidivism? What is the District asking its federal partners to do on this issue?

What is CSP planning to change to address this increase in recidivism?

Why is GPS utilization so low among the CSP population, even those that are under “maximum” supervision?