The US Attorney's Office declined to prosecute 2/3 of the people that MPD arrested

Why is there so much disagreement between federal and local law enforcement?

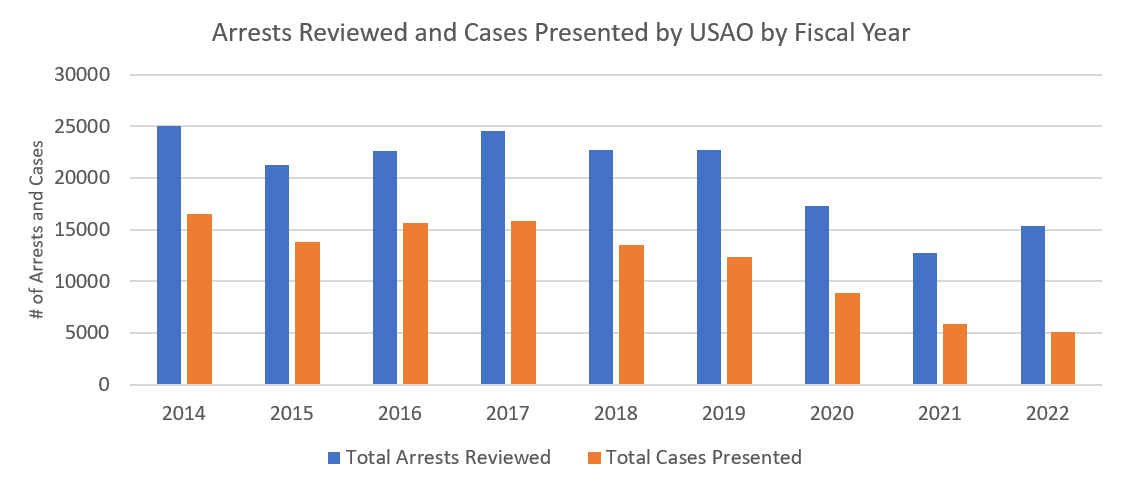

Prosecutors have enormous power in the criminal justice system. In DC, most of this power resides within the Superior Court Division of the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO) of the District of Columbia. They decide which cases to charge and how the government presents its evidence. In recent years, this division has declined to prosecute a growing share of MPD’s arrests so that now most arrests don’t result in charges:

In the most recent complete fiscal year (2022), USAO prosecutors “declined” 67% of all arrests; i.e. they reviewed the arrest and declined to press charges. This represents:

52% of felony arrests

72% of misdemeanor arrests

FY 2022 continued a trend of higher and higher declination rates that began in FY 2018 and continued under both Trump and Biden administration appointees

The USAO’s declination rate went from 31% in FY 2016 (Obama appointee) to 48% in FY 2020 (Trump appointee) to now 67% in FY 2022 (Biden appointee)

This increased declination rate is happening as the overall arrest rate is going down. Despite fewer arrests to review, prosecutors are still taking on a smaller share of them. As a result, the number of cases the USAO brings is down 68% from FY 2017.

The USAO isn’t “winning” a higher share of the much-smaller pool of cases they are taking on; suggesting that this trend isn’t simply them triaging the weakest cases

Source: Every fiscal year the US Attorney’s Office posts their Annual Statistical Reports. Somewhere around page 67 in each report is Table 17 detailing the actions of the Superior Court Division. The data we’re focusing on today is at the top, where it breaks down “Arrests Reviewed” by felony or misdemeanor and then says how many were “Presented” (i.e. the prosecutor made a case) or “Declined” (no charges):

If we track these reports over time we see a clear increase in the % of “reviewed arrests” that the USAO declined to charge:

It was not that long ago that the vast majority of felony and misdemeanor arrests led to some kind of charge. Now a large majority of misdemeanors and even a slight majority of felony arrests simply result in no charge. This is a massive policy change and it’s one that was made completely outside of the authority of Mayor Bowser, Chief Contee or the DC Council.

The Superior Court Division in the USAO reports to the US Attorney for the District of Columbia; which is a political appointment. It’s notable that about half of the trend towards decreased prosecution happened under Trump appointees; Republican “tough on crime” rhetoric is generally at odds with prosecutors exercising restraint. And Channing Phillips, the Biden appointee for about half of FY 2021, was previously the US Attorney for DC in FY 2016-2017 when the office was prosecuting a much higher share of arrests. It would take investigative reporting to figure out why this happened because who was in charge doesn’t provide any obvious answers.

It’s also worth pointing out that with overall arrests down as well (more on that in a subsequent post), cases presented by the USAO are down 68% since FY 2017:

One possible explanation for this trend could be if the USAO had been losing a lot of weak cases that it was “presenting” and had cut back on those weak cases in recent years to focus on “winning” the important ones. However, there hasn’t been a massive increase in the % of cases that end in a guilty plea or verdict (especially compared to the much larger increase in declinations). So that possible explanation doesn’t really hold water:

This USAO data shows that there has been a large policy change when it comes to prosecution in Washington, DC. What we can’t answer directly is why this change occurred and its impact:

In general, the “certainty of punishment” is a key part of deterring crime. If criminals believe that even if arrested they won’t be charged, then that could drive up crime rates.

With 2/3 of arrests not leading to a charge it means that the millions of MPD staff hours went into those arrests likely didn’t help much. Understanding why MPD’s standard for “this warrants an arrest” has diverged massively from the USAO’s standard for “this warrants pressing charges” in recent years is key. Prosecutors should not be taking up 100% of cases but this change is in comparison to DC itself just a few years ago so it’s a valid benchmark.

This change in prosecuting behavior has a much more immediate impact on punishment than any of the proposed changes to the criminal code since this is going on right now; rather than going into effect in future years.

Possible Questions for Interested Legislators and Journalists:

What policies changed at the Superior Court Division of the USAO that drove this large increase in the % of arrests that are declined? Is this the intended outcome and does Chief Johnston want to continue this rate of declinations?

Has there been an increase in diversion or other alternatives to prosecution that can explain this shift?

Have there been changes in the quality of evidence provided by MPD that has prompted prosecutors to decline or dismiss cases? Are there specific problems, departments or officers that MPD should focus on?

Note the Washington Post has a recent story on this problem that’s worth a read: https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/03/13/dc-police-gun-cases-dropped/

For FY 2021 and 2022, did the demands of the January 6th investigations (also run by the USAO DC) divert resources away from “local” DC crimes?

Note the DOJ requested 130 additional FTEs in FY 2023 for these investigations that are run through the DC office: “Funding is critically needed to provide the USAO-DC with additional prosecutors and support personnel to respond to the increased caseload, litigation costs, and other court proceedings arising from these cases.”

In future posts we’ll be looking at the “pipeline” from crimes to arrests to prosecution in addition to getting back to how MPD staffing corresponds with where crime occurs. As always thanks for reading and please share these posts if you found them useful.

Here's one explanation for the huge drop in cases that are accepted for prosecution, but it's an explanation that won't get a lot of political attention -- officerless papering.

I worked in the this USAO doing misdemeanor prosecutions in 2015. The process of accepting a case for prosecution is referred to as "papering" the case, and in 2015 this was an in-person, physical process. For misdemeanor cases, what would typically happen is the following: A particular individual was arrested by DC police overnight. That individual was brought into the stationhouse and booked. If he was being booked for 2 or more misdemeanor offenses, or if he had a record of failing to appear in previous cases, he would be held overnight (this was common). Otherwise, he would be issued a citation and given a court date for his arraignment. On a given weekday, there might be 50 to 100 defendants who were held overnight and charged, and another dozen or fewer who were issued a citation.

The following morning, arraignment court would be held, and everyone who had spent the night in the stationhouse holding cell was brought down to the the Moultrie courthouse and arraigned on charges. In order for those charges issue, a criminal complaint had to be drawn up, together with a Gerstein affidavit (i.e., the sworn affidavit signed by the arresting officer that details the circumstances of the arrest and the basis for the charge). The officer had to physically come to the courthouse and sit in the basement, along with the charging AUSA, while this Gerstein was filled out and signed. The charging AUSA had immediate access to the officer, and got to ask him questions, track down leads, and flesh out the factual basis for the crime while the events were still fresh in the officer's mind.

This process changed starting in 2016. In 2016, MPD and the USAO moved to officerless papering. The police report would be dropped off or sent electronically to the USAO, but no officer was required to come to court in order to charge the defendant. The AUSA could only charge the case based on what the paperwork said. If the paperwork was vague, incomplete, inaccurate, or inconsistent, the case would simply be no-papered. There was no immediate resource that the charging AUSA could use to close gaps, fix errors, etc. The case simply lived or died based on paperwork.

Why the change? I don't know. I can say that officers *hated* papering cases in-person. They would be out on duty all night, arresting people at all hours of the morning, only for their shift to end, but then they were required to come to court. Papering was not a quick or efficient process. The officer might have to wait around in the courthouse basement for hours, waiting for the charging AUSA to get to their case. It was a huge pain. But it absolutely made for better-charged, more thoroughly developed cases.

I am a victim of a felony armed robbery last year with overwhelming evidence in the case and the USAO refuses to press charges or even respond to my phone calls. And local media doesn’t care either!