The US Attorney's New Spin

"the overall charging rate isn’t what we should be focused on”

Over the last week there’s been a whirlwind of new prosecution data that has coincided with a media offensive by the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO). This post will review the latest data and some of the ways the USAO is trying to shape the political narrative to their benefit. Here are the latest prosecution data releases:

October-December 2023 USAO Prosecution Rates

Fiscal Year 2023 USAO Prosecution Data

DC Sentencing Commission Analyses of Firearm and Theft Prosecutions

On Thursday the USAO released new prosecution data for October-December 2023 that showed they charged 55% of suspects on the day of arrest; meaning that 45% of arrests resulted in no charges from the USAO at that time. This is the most recent prosecution rate we’ve received even though it’s now over 2 months old because the USAO refuses to publish prosecution rates as part of their monthly reports. This 55% prosecution rate was an increase of just 2% from the previous quarter and is significantly lower than the 73% average between 2003-2013:

The USAO also claims they sent another 4% of cases “for prosecution elsewhere” and therefore are claiming an “effective prosecution rate” of 59%. The historic data does not include this 4% “bonus” (nor do we know if those cases are prosecuted when they are transferred elsewhere) so for apples-to-apples comparisons this post will use the 55% day-of-arrest figure.

This 2% increase in the prosecution rate is a bit underwhelming relative to the framing that “prosecutions will continue to rise in the current fiscal year” that was the message the last time USA Graves released prosecution rate data back in October 2023:

“In the last three months of the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, Graves said, his office prosecuted 53 percent of arrests, and he said he believes that prosecutions will continue to rise in the current fiscal year.”

The USAO’s messaging at their data release press conference was an interesting mix of narratives:

USA Graves discussed how crime is falling: "Some of these things are historic levels of improvement,” Graves says. “I’m not saying we’re going to end up there. But if you got to a 36 percent reduction in homicides year over year at the end of the year, you would be hard pressed to find another jurisdiction that had that much of a drop at any point in time. Anything close to that would be historical.”

USA Graves made some conflicting arguments about the crime lab. On the one hand he attributed the prosecution rate partially to the crime lab’s loss of accreditation: “No other city that I’m aware of had its lab implode” which implies that the lack of evidence testing led the USAO to decline to prosecute otherwise-viable cases. On the other hand he claimed that his office had “effectively built a makeshift DFS” (DFS = DC’s Department of Forensic Sciences) to test evidence and that therefore DFS recent re-accreditation (for DNA and drug testing) wouldn’t raise the prosecution rate: "So it’ll be helpful, but it’s not going to impact the charging numbers.”

It seems like the USAO wants credit for backfilling DFS’ capacity but that also implies some responsibility for evidence testing. Since prosecution volumes were at record-lows in FY 2022 this suggests the USAO didn’t mobilize all of its evidence testing resources until after they came under intense Media/Congressional scrutiny in 2023.

USA Graves explicitly downplayed the importance of the charging rate: “We’re trying to convince you: focusing on the overall charging rate isn’t what we should be focused on” and that prosecution rates are “not in the top 50” factors that impact crime

It may sound odd seeing a prosecutor not jump at the chance to take credit for a decrease in crime that corresponds with an increase in prosecution. But the underlying political motive here is that USA Graves likely prioritizes avoiding blame for the Spring-Summer 2023 crime spike after prosecution rates hit record lows in Fiscal Year 2022. Therefore he’s essentially “stuck” arguing that a pretty core prosecutorial metric doesn’t isn’t that important in order to avoid acknowledging any responsibility for DC’s problems last year.

Interestingly, in Harry Jaffe’s piece in The Atlantic (more below) Graves admitted that “We all viewed the 33 percent as a problem.” So Graves can admit that only prosecuting 33% of arrests was “a problem” in the abstract but simultaneously has to downplay that prosecution rates have a significant impact on crime rates.

There’s a strong research consensus that the certainty of punishment deters crime and there’s specific research finding “that prosecutors’ effect on the certainty and celerity of punishment was associated with lower levels of crime, whereas their effect on the severity of punishment was not.”

USA Graves pointed out that increased detention is incapacitating criminals and putting downward pressure on crime: “We are taking enough people off the streets that at a point you will start to see the impact of it, and I think we have reached that point”

As of last Friday the DC jail population has increased by over 600 people (+51%) since March 2023. This increase in the jail population seems to be driven much more by increased arrest and prosecution rates than changes to pretrial detention guidelines; which contradicts the USAO’s main point that the prosecution rate isn’t a key factor:

USA Graves repeated his past messaging implying that some convictions that result in probation aren’t a real consequence: “When the result of the prosecution, because of the way the system is designed, is that the bulk of people are not experiencing some kind of consequence, that can unintentionally send a signal that getting caught is not that big of a deal”

This appears to be an effort to reframe a “we should increase the severity of punishment” argument for longer prison sentences in the rhetoric of “we should increase the certainty of punishment” in order to be more appealing to Washingtonians.

Note that 80% of people on Probation/Parole/Supervised Release stayed arrest-free during their supervision last fiscal year. Probation is definitely inappropriate for some higher-risk defendants but it’s an exaggeration to claim that it isn’t “some kind of consequence.”

The USAO shared an analysis that they claimed showed that their prosecution rate was comparable to states with similar laws regarding mandatory arrests for domestic violence:

We’ll review this analysis more below but in short the USAO compared their most recent (and favorable) prosecution rate to data points from a few select cities in each state they deemed “comparable”

The “mean day-of-arrest charging rate across these states is roughly 54%” which still proves that the USAO in DC was an outlier when they only prosecuted 33% of arrests in FY 2022 and 44% of arrests in FY 2023.

This mix of messages resulted in some interesting headlines. The Post headline focused on the unusual claim that the increase in the prosecution rate wasn’t related to DC’s concurrent drop in violent crime:

This press conference was well-timed for the USAO since it got their message out ahead of two media items that presented a less-rosy view of prosecution in DC:

The Post Editorial rightly questions the validity of some of the USAO’s reasons/excuses for the lower prosecution rate. USA Graves likes to claim that many of the declined cases are due to DC’s mandatory arrest laws regarding domestic violence. In October 2023 he claimed there were “over 1,000” cases per year where they had declined prosecution because it was domestic violence and the victim didn’t want to press charges; which in a city with over 15,000 adult arrests per year isn’t a large % of potential cases. However now in March 2024 Graves told the Washington Post “half of uncharged arrests arise from domestic violence calls” which would imply there are over 3,000 such cases a year. The fact that the stated number of supposedly not-prosecutable domestic violence cases fluctuates 3X depending on the circumstance should cast some doubt on the validity of those numbers. And as others have pointed out, DC’s mandatory arrest laws haven’t changed in years so they don’t explain why the USAO’s prosecution rate is still so far below the historic DC average. In any event this is yet another reason why Washingtonians deserve transparent data about arrests and prosecutions so that we can have a debate grounded in evidence and data rather than spin.

The USAO’s fixation on DC’s domestic violence laws possibly has more to do with invalidating unfavorable comparisons to jurisdictions like Philadelphia, Chicago and New York with much higher prosecution rates. New York does require arrests for “felony conduct” in a domestic violence situation but rather than try and adjust for whatever small % of arrests may be non-prosecutable the USAO prefers to throw out New York comparisons entirely; probably because every county in New York state has much higher prosecution rates than DC.

Even when comparing to jurisdictions the USAO deems “comparable” it’s not as clear-cut as their analysis suggests. The USAO analysis claims that “Louisiana” only prosecuted 49.5% of arrests. After some research, it turns out that this was based on data from Orleans Parish (New Orleans) specifically for the years 2021 and 2022 (when the USAO was declining to prosecute 67% of arrests). The 2021 and 2022 data appear correct but the USAO neglected to update the data to reflect the fact that the Orleans Parish District Attorney only declined to prosecute 36.5% of cases in 2023; a full 8.5 percentage points lower than the USAO in DC today. This suggests that there is still room to increase the prosecution rate and is another example of cities running circles around DC when it comes to data transparency:

The USAO analysis claims that “New Jersey” is a state with comparable laws who declined to prosecute 64% of arrests. This number is so high that if true one wonders how it wouldn’t already be a scandal. It turns out that this was specific to data from the Essex County (Newark) Prosecutor and compared the number of indicted defendants (in the numerator) to the number of “case files reviewed” in the denominator. However, in New Jersey only counting indicted defendants excludes a huge share of charged defendants which would cause their prosecution rate to look artificially low:

“In New Jersey, offenses are not categorized as felonies, misdemeanors, and infractions but rather as indictable crimes, disorderly persons offenses, and petty disorderly persons offenses. Disorderly persons offenses and petty disorderly persons offenses are similar to misdemeanors in other states, because they are less serious offenses, punishable by less than six months in jail. Indictable offenses closely resemble felonies and serious misdemeanors in other states.”

In New Jersey’s Municipal Court Statistics there were 2X as many new filings for those “Disorderly Persons” and “Petty Disorderly Persons” offenses (which are similar to the Misdemeanors that make up most of DC’s cases) as filings for “Indictable” offenses. So excluding those prosecutions from the numerator while still counting those arrests in the denominator would skew the calculated prosecution rate.

The Essex County prosecutor unfortunately doesn’t include any information about these missing non-indictable prosecutions but the Mercer County (Trenton) prosecutor helpfully provided a breakdown:

Out of 5,117 cases reviewed, they secured 1,222 indictments. If we only counted indictments (like the USAO did for “New Jersey” aka Essex County) this would be a 24% prosecution rate and a 76% “declination” rate; similar to the shocking 64% declination rate they claimed for “New Jersey”

However, “2,383 defendants with indictable charges were approved for presentation to the grand jury” which would imply a 47% prosecution rate if we counted each of those defendants as “charged” since the prosecutor chose to move forward with the case

Note that 99% of defendants actually “presented” to the grand jury were indicted. So the huge gap between the large number of defendant’s “approved for presentation” and the number “indicted” appears to have been due to factors (possibly scheduling since this is from 2021 when COVID restrictions limited court operations) other than the quality of the cases.

In addition “1,842 defendants were administratively downgraded to disorderly persons offenses and referred to municipal court or the Remand Program for prosecution.” If we add up the defendants approved for presentation to the grand jury and those referred for prosecution we’d have an 83% prosecution rate.

The reason this side-quest into New Jersey law is relevant at all is that the USAO appears to be using a misleading view of prosecution data from other “comparable” states to justify their own low prosecution rates here in DC. I could also be making errors about these other states so I am reaching out to experts in those states to try and further test the USAO’s analysis. For what it’s worth, the number of unique arrests (97K) vs. the number of unique defendants charged (76K) in New Jersey in 2023 implies a 78% prosecution rate; much higher than both the USAO in DC and the value they ascribed to “New Jersey” in their analysis:

Given how different these prosecution rates appear to be from the USAO’s portrayal one hopes there will be some more scrutiny of the USAO’s claims in the future. However the USAO managed to gets some variation of the line “the D.C. rate is comparable to a sampling of nine states with mandatory domestic violence arrest laws that publicly report their prosecution data” into stories from the Post, WTOP, ABC7 and the Washington City Paper. So regardless of the accuracy of their analysis, the USAO succeeded in getting their narrative out there.

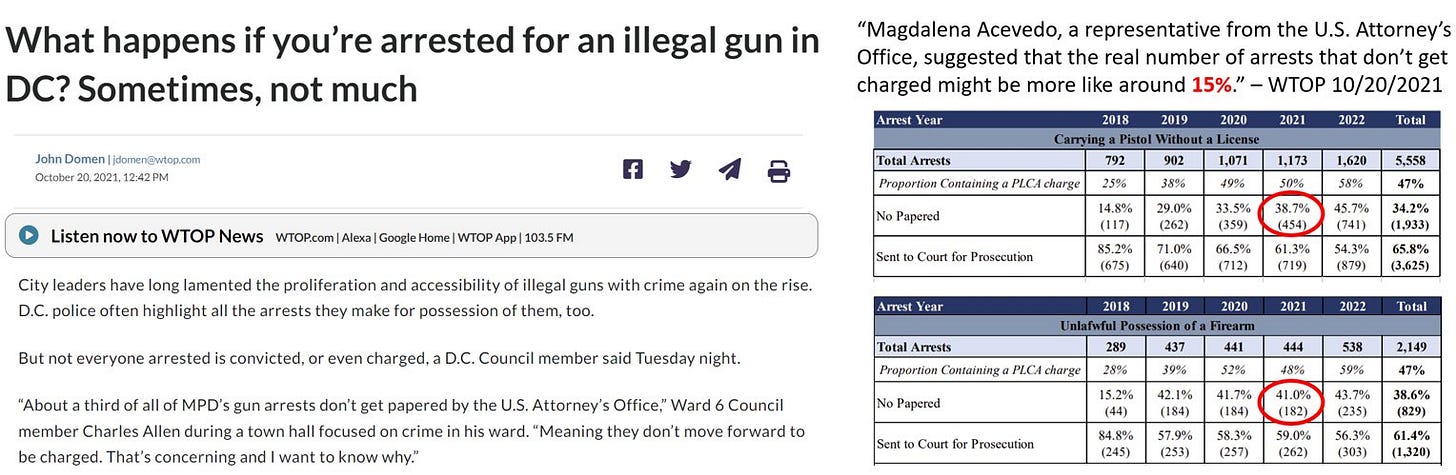

Another reason that DC media should be skeptical of the USAO is that they have a track record of misleading the public about prosecutions. In October 2021 CM Charles Allen pointed out that “About a third of all of MPD’s gun arrests don’t get papered by the U.S. Attorney’s Office,” Ward 6 Council member Charles Allen during a town hall focused on crime in his ward. “Meaning they don’t move forward to be charged. That’s concerning and I want to know why.”

However, “Magdalena Acevedo, a representative from the U.S. Attorney’s Office, suggested that the real number of arrests that don’t get charged might be more like around 15%.” This meeting was taking place in late 2021 and the USAO’s firearm offense prosecution rate had been in free fall for almost 3 years at that point. In this case we had DC’s local government trying to raise an important issue about the performance of our unelected Federal prosecutor and the USAO simply presented misleading statistics and the media moved on. As we will see below, USAO firearm prosecutions increased a lot once they finally paid a political price in 2023. But unfortunately the media let them off the hook in 2021 and the problems only got worse with disastrous effects for DC.

After the USAO had flooded the zone with their Thursday press conference they also published more Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 prosecution data:

Their 60% prosecution rate for felonies was 21% (in percentage points) below the 2003-2013 average and up 13% from the previous fiscal year

Their 36% prosecution rate for misdemeanors was 35% below the 2003-2013 average and up 8% from the previous fiscal year

This shows that the effort to increase prosecution rates in 2023 was (rightly) focused on felonies. The USAO’s previous FY 2023 data releases hadn’t split out felony and misdemeanor prosecution rates.

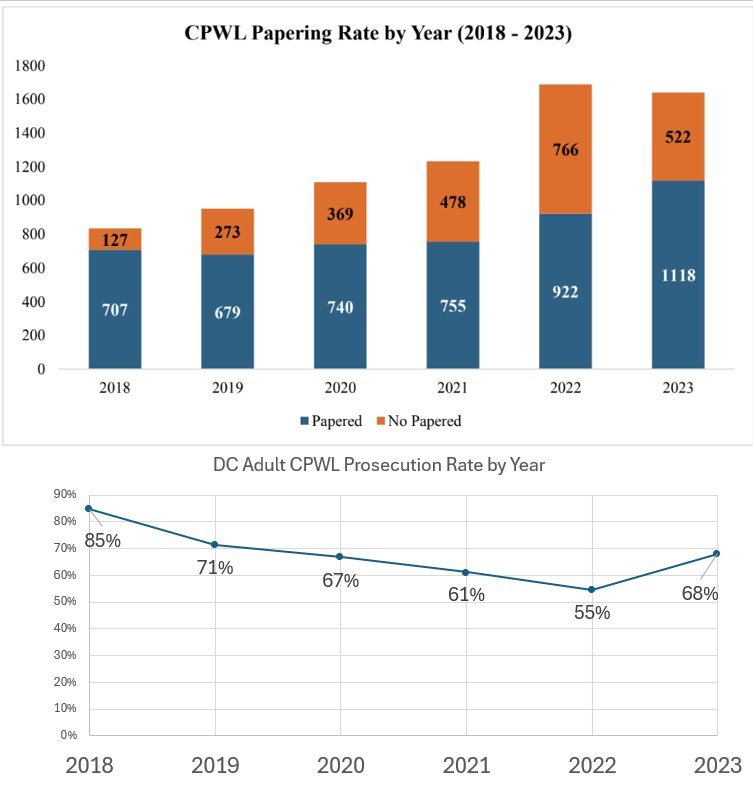

The 2023 increase in felony prosecutions (again, after the USAO came under pressure) is welcome and is something we see replicated in a new firearms offense analysis by the DC Sentencing Commission. This is one of two recent analyses that are in circulation and appear to be genuine but aren’t yet posted on the Commission’s website (though I hope they will be soon). Thanks to Cully Stimson for requesting this analysis that helps show the decline and partial rebound in CPWL prosecution rates; as well as the massive increase in arrests as more illegal guns have poured into DC:

The 13 percentage point improvement in the CPWL prosecution rate in 2023 basically reversed 2 years worth of decline. Since the USAO mostly started increasing prosecution rates after they came under scrutiny in mid-2023 there’s reason to hope that the 2024 data will look even better.

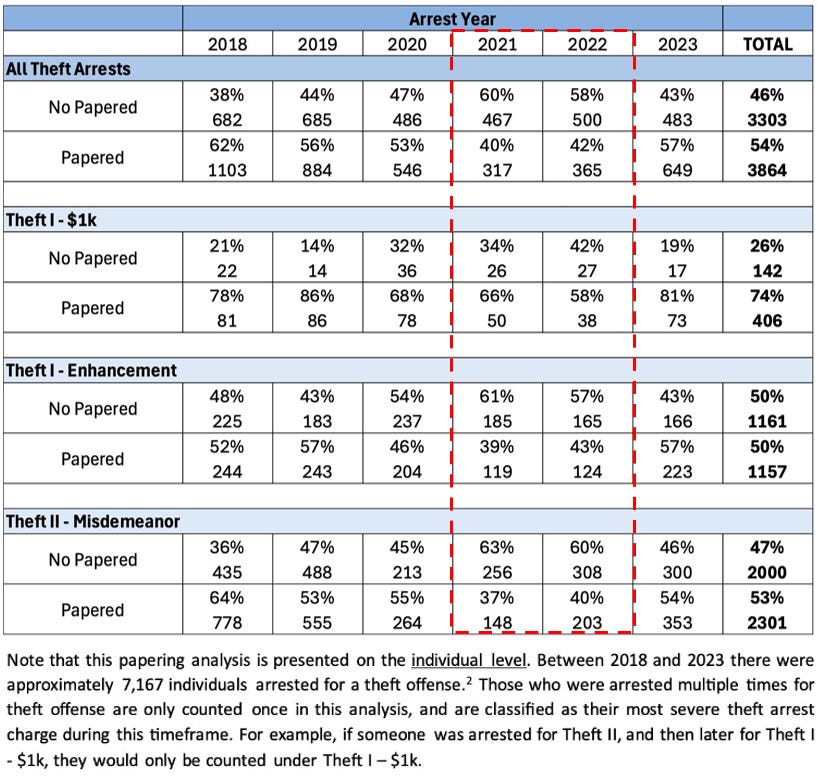

Finally, the DC Sentencing Commission also produced an analysis of the USAO’s theft prosecution rates:

The USAO declined to prosecute 58%-60% of all adult arrests for theft in 2021 and 2022. Every media story about “out of control theft” ought to mention how the USAO undermined the certainty of punishment for theft in DC.

Prosecution rates rose 15 percentage points in 2023 to 57% but are still below 2018 levels; especially for Theft II Misdemeanor

Under DC law repeat theft offenders face harsher penalties, including a mandatory minimum sentence, but only if the USAO secures those convictions. This is an example of where the USAO’s apparent disdain for lesser offenses means they fail to build the criminal history to get the longer sentences they say they want.

Suspects arrested for theft still have slightly worse odds than a coin flip of getting away with no charges being filed

Thankfully we have seen real improvements in the USAO’s prosecution rate over the last year thanks to public pressure. It was just over one year ago (March 14th, 2023) that this Substack first reported that the USAO had only charged 33% of cases in FY 2022 and helped kick off greater scrutiny of their operations. Before the USAO got hit with a mountain of bad press for their local prosecution rates there were no indications that they were planning to proactively address them. In early March 2023 the USAO’s media outreach was stressing a “white collar pivot” rather than focusing on DC crime:

All of the improvement in prosecution rates since March 2023 happened before any significant changes in DC law or the USAO’s resourcing. Even the positive steps to improve evidence testing and MPD training are still indictments of the USAO’s (and the Bowser administration’s) failure to proactively deal with those problems before the abysmal 33% prosecution rate ended up in the Washington Post and in Congressional hearings. So far we’ve seen that when it comes to the USAO, pressure yields results. The USAO’s behavior is reminiscent of how audience members react to an old motivational speaker trick: The speaker will tell the audience to “stand up, raise your arms and reach as high up in the air as you can”…the audience complies and after a pause the speaker says “raise them a little higher” and people will generally stretch a little more or stand on their toes and in fact “raise them a little higher.” The point is that people will think they are doing all that they can and when pushed they often find they can do a little more.

The USAO’s spin is that they are doing everything they can. But they’ve proven to be an unreliable source and there’s a lot of evidence that suggests they could do more to charge and secure meaningful convictions in more cases. We should insist they try a little harder.

you should apply for a grant: https://www.macfound.org/press/grantee-news/press-forward-announces-first-open-call-for-newsroom-grants

Thanks as always for this insightful analysis!