Mixed signals on pretrial detention

A small change in policy turns out to have a very small impact

Pretrial detention is one of the most debated issues in crime policy in DC but often the argument is about theoretical extremes rather than the actual nuts and bolts of operations. Thankfully the Pretrial Services Agency (PSA) released some new data that covers both longer term trends in pretrial release and some initial data on the Summer crime bill’s expansion of pretrial detention. Surprisingly, DC judges were actually increasing their use of pretrial detention before there were any legislative changes.

Federally-appointed judges are the ultimate decisionmakers for pretrial detention in DC. Judges weigh the defendant’s risk to the public and to not appear in court, supported by a risk assessment/recommendation from PSA, when deciding to detain a defendant or release them (possibly with specific conditions) before trial. The chart below from this post helps explain who is involved at this stage in the process:

PSA states their mandate as “We recommend the least restrictive conditions that promote public safety and return to court.” Judges’ decisions are technically shaped by the “rebuttable presumptions” in DC law that say a judge should default to detaining a suspect who is accused of particular crimes unless the defendant can prove they are not a threat to the public or a flight risk. The longstanding legal language is “There shall be a rebuttable presumption that no condition or combination of conditions of release will reasonably assure the safety of any other person and the community” if the judge finds probable cause that the defendant:

Even though the law may say the “default” or rebuttable presumption is that certain defendants should be detained; judges are free to rule that the defendant’s arguments have rebutted the presumption and order pretrial release anyway. This is particularly common in cases like Carrying a Pistol Without a License (CPWL) according to the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO):

”In the District, people charged with illegally possessing a firearm are typically released pending trial—even when they have previously been convicted of a felony. While there is a presumption in the D.C. Code that these individuals will be detained pending trial due to the inherent dangerousness of firearms offenses, most are released.”

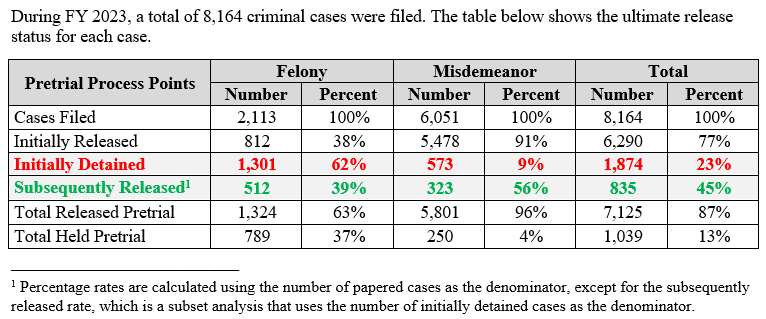

The vast majority of people detained pretrial are accused of felonies, not misdemeanors. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2023 37% of felony defendants were held pretrial while just 4% of misdemeanor defendants were held. Despite significantly more misdemeanor cases, there were 3X as many detainees accused of felonies (789) as misdemeanors (250):

Felony offenses are a much broader category than the offenses with rebuttable presumptions of detention so when we narrow down to “defendants charged with violent crimes” we see much higher detention rates:

For most of FY 2023 before the “Prioritizing Public Safety Emergency Amendment Act of 2023” (the PPSEA or Summer crime bill) went into effect DC judges were detaining 64% of defendants charged with violent crimes

This was already a 14% increase since FY 2019. This increase doesn’t appear to be driven by legislation but possibly by changes in the composition of cases brought by the USAO and judges’ assessment of defendant risk.

In the 2 months and 10 days of FY 2023 after the PPSEA was in effect judges detained 71% of violent crime defendants; a 7% increase.

After this increase in detention “the arrest-free rate remained stable” among those defendants that were still released.

Of 897 defendants who were both 1. Accused initially of a crime of violence and 2. Released pretrial PSA says that “1.2% were rearrested for a crime of violence.” This suggests that there were ~11 defendants in this rearrested cohort. Those rearrested suspects could be accused of multiple violent crimes while on release; but given that DC had 5,336 reported violent crimes in 2023 it’s unlikely these 11 rearrested defendants are driving more than 1% of violent crime.

If 897 “crime of violence” defendants were released and they were 36% of all “crime of violence” defendants that implies there were ~2,492 total such “crime of violence” defendants in FY 2023. Therefore the 7% increase in the pretrial detention rate (seemingly due to the PPSEA) would impact ~174 defendants per year.

This would represent an ~17% increase in the number of defendants detained pretrial and we’d expect about 2 of them (out of the 174) to be re-arrested for a crime of violence if they had instead been released pretrial

Since the longstanding rebuttable presumption language already covered a broad swath of violent and firearms offenses, one of the main changes in PPSEA was to expand it to crimes of violence that don’t involve a firearm. It makes sense that this relatively small change only increased the pretrial detention rate by 7% in the very little data (2 months and 10 days) that we have. It’s also not surprising that “the arrest-free rate remained stable” for the remaining population of released defendants given that:

The marginal change in policy only detained a few extra people

92% of all defendants on pretrial release remain arrest-free anyway

There hasn’t been much time to assess a change if in fact there was one

Of course proponents of expanding pretrial detention would want to see the “arrest-free rate” increase since that would imply that the extra detention was targeting people disproportionately likely to engage in (more) crime and get rearrested. The pretrial detention expansion still may have prevented a few crimes; but given the relatively small numbers it’s likely that increased arrest and prosecution rates had a much larger role in DC’s recent reductions in crime as discussed in this post:

In general the logic to apply the rebuttable presumption (which is far from a guarantee of detention) to unarmed crimes of violence makes sense. On the other hand the proposal to have the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC) study the impact of this change before making it permanent is also reasonable. As of the Secure DC bill’s first reading (and the amendments that passed as of that date), the currently-in-place expansion of pretrial detention would extend until August 29th, 2024 with the CJCC completing a study on its impact before that date.

Before delving into the rather dysfunctional politics of pretrial detention, it’s worth noting that there seems to be sincere belief among some policymakers that expanding detention has helped reduce crime and equally sincere belief among others that it hasn’t helped at all. Expanding detention is something direct and concrete where proponents can say “because we detained these people they could not commit any additional crimes in the community.” It’s also plausible to claim that the harms of detaining potentially-innocent people outweigh the potential reduction in crime given the relatively low rearrest rates. However there is actually broad consensus among policymakers that some defendants should be detained and others are fine to be released pretrial. The policy disagreements about where exactly to draw the line are relatively modest.

The politics of pretrial detention:

DC’s dysfunctional crime debate however has wildly exaggerated the scope and stakes of the pretrial detention debate. Remember that most people accused of a violent crime were already being detained pretrial and this modest expansion of pretrial detention is estimated to prevent ~2 rearrests for a crime of violence per year. However in the Mayor’s messaging to ANCs (thanks to ANC Joe Bishop-Henchman for providing updates from the meeting) this is played up as a key driver in reducing crime: “after it went into effect, we saw a decrease in crime.”:

The last sentence is particularly misleading. DC judges already consider if “the person poses a danger to the community if released as they await trial.” The implication is that this amendment would prevent judges from considering the danger to the community when in reality the phrase “safety of any other person and the community” is found throughout the permanent code governing pretrial detention. Even some misdemeanor defendants are detained pretrial exactly because they are a danger to the community or a flight risk. The actual policy debate is over which specific offenses have a rebuttable presumption of pretrial detention.

The other claims from the Mayor’s team fall more into the realm of regular political messaging. The expansion of detention did in fact coincide with a decrease in crime. We’ve discussed how it’s likely that changes at MPD and the USAO were probably bigger drivers of DC’s reduced crime rates in the 2nd half of 2023 but there’s nothing wrong with their claim. Where this messaging tends to be misinterpreted by Washingtonians is they often think that before this legislation most defendants accused of a violent crime were being released pretrial and that not extending it will mean a huge release of alleged violent criminals. That wildly oversells the scope of the debate of the debate but is a very effective political message.

When Opportunity DC, an “independent expenditure committee” that supports DC’s business community, published a poll in November 2023 they included a question about pretrial detention. In that poll 84% of voters either “strongly” (59%) or “somewhat” (25%) supported “stricter bail requirements for those charged with violent offenses”:

One can quibble with the question framing and possible bias (Opportunity DC is supporting the Secure DC legislation) but it makes sense that this kind of proposal polls well. So we’re likely to hear more about pretrial detention because it’s an easy way for politicians to look “tough on crime.”

On the other side of the debate some opponents of Secure DC have also inflated the extent of the pretrial detention expansion and the policy stakes:

They claim “this provision would dramatically expand the number of people this applies to.”

They cite the Office of Racial Equity’s claim that “pretrial detention does not promote public safety.”

They ask the Council to “work to put a complete end to pretrial detention in the future to ensure that no one loses a day of school, work or childcare when they haven’t even been proven guilty of a crime.”

The plain language of the call for “a complete end to pretrial detention” would seem to apply to even the most serious violent crimes like murder, assault with intent to kill and rape; and as such would almost certainly never pass. But it reflects a mindset where “carceral solutions” can’t solve anything so therefore there are no costs to rolling them back. But there are certainly defendants who are a danger to the community and detaining them pretrial is the least-bad option. Many of the studies arguing for reducing pretrial detention are about relative reductions; not abolition. In New Jersey for example they adopted a system that sounds like what DC tries to do: “On any given day, there are thousands fewer defendants in jail, with only the highest-risk defendants and those charged with the most serious offenses detained.” It’s still an important finding that in some cases states or cities can be smarter about pretrial detention. But that in no way implies that we could abolish pretrial detention and not see harmful impacts to public safety. Opponents like to cite that PSA’s arrest-free rate is so high (which is a good thing) but one reason that it’s high in the first place is that some of the highest-risk defendants are detained pretrial.

There’s a valid debate to be had about where we draw the line on pretrial detention, but pretending that it’s either a silver bullet to solve crime or a completely pointless exercise doesn’t help. We’d really benefit from comparisons with other cities and states to see how other jurisdictions are trying to strike the right balance. The “best” thing about this debate is that actual conditions on the ground have improved so that now politicians are trying to claim credit for “a decrease in crime” rather than playing the blame game. So far in the first two months of 2024 reported violent crimes are down and in line with the least violent years in recent DC history:

There are no guarantees that relatively low violent crime rates will continue. However in past years the January-February data has been relatively predictive (with a R-squared value of 0.61) of the violent crime rates for the whole calendar year so that’s some cause for optimism. On the other hand last year we also had a relatively calm January-February before a serious Spring-Summer crime spike.

Compiling this data also reinforced just how rose-colored our view of the past has become. In DC’s boom years in the 2010s we had a lot of reported violent crimes.

The reported property crime rates are more variable and the January-February data seems to be much less predictive of calendar year crime rates:

With violent crimes, robberies are now back down to the levels we saw in 2017-2022 (after an unprecedented spike in 2023) and ADWs are at record lows:

With property crimes, generic Theft/Other is unfortunately back at pre-COVID levels. On the positive side, motor vehicle theft continues to drop from last year’s surge and both “theft from auto” and burglaries are close to record lows:

Pretrial detention policy certainly didn’t cause the 2023 crime spike and the modest expansion of pretrial detention is likely only a minor factor in the recent decrease in crime. Hopefully the political rush to claim credit for falling crime in DC doesn’t take the pressure off of the operational problems in our criminal justice system, especially with how we handle the highest-risk suspects in DC. Thanks again to everyone who has shared this blog with others as we come up on the 1 year anniversary of this publication!

Doesn’t using the re-arrest rate assume that those released pre-trial who commit new crimes are actually caught?

Thank you for a wonderfully nuanced article on the issues. But I still can’t reconcile something: Many of your posts state that people arrested for violent crimes often have multiple prior arrests. But you seem to be saying that pre-trial detention has a marginal impact on reduction of violent crime. Only 1.2% were re-arrested for violent crime? What am I missing? How does this mesh with your prior claims that many people arrested for violent crime have multiple prior arrests?