How even serious violent crimes fall through the cracks

Very few arrests lead to convictions for serious offenses

While property crimes represent ~85% of all reported crimes in DC; many people are more concerned about serious violent crimes like homicide, felony assault and carjacking. The combination of closure rates, papering decisions, conviction rates and plea bargaining often leave the perpetrators of these crimes free to victimize other people. Focusing efforts to solve these crimes and win meaningful convictions will likely do more to deter and prevent violent crime rate than adjustments to the sentencing guidelines.

Last week we discussed how the “certainty” of punishment was the best deterrent for crime. The Department of Justice has a useful explainer and the first two points are especially relevant:

“1. The certainty of being caught is a vastly more powerful deterrent than the punishment.”

“Research shows clearly that the chance of being caught is a vastly more effective deterrent than even draconian punishment.”

“2. Sending an individual convicted of a crime to prison isn’t a very effective way to deter crime.”

“Prisons are good for punishing criminals and keeping them off the street, but prison sentences (particularly long sentences) are unlikely to deter future crime. Prisons actually may have the opposite effect: Inmates learn more effective crime strategies from each other, and time spent in prison may desensitize many to the threat of future imprisonment.”

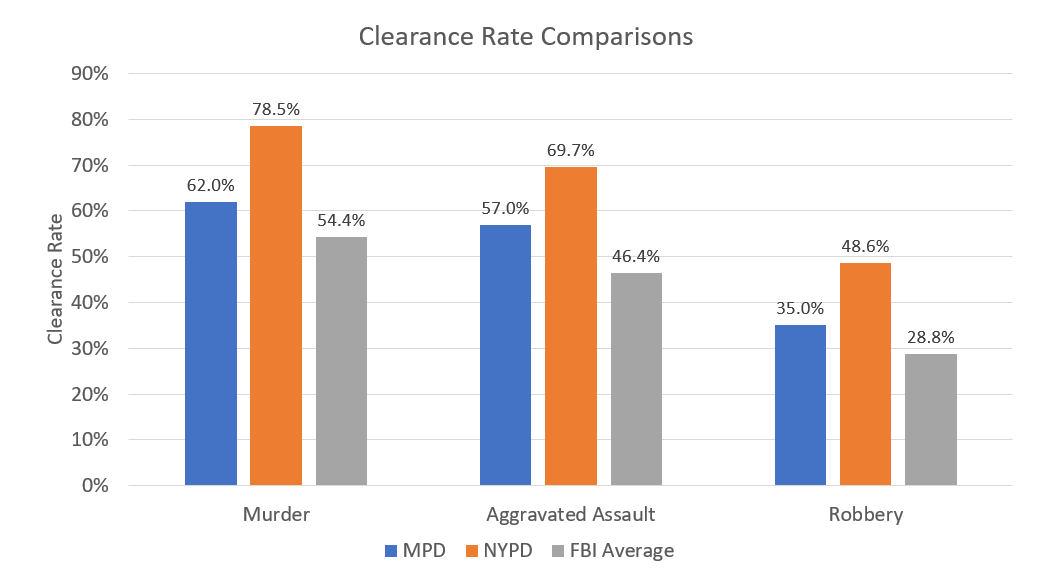

The main impact of prison sentences on future crime rates is by “keeping them off the street” rather than deterring people ahead of time. Another term that people use to describe this crime-fighting aspect of prisons is “incapacitation” which is an aptly harsh term. But for either “certainty of being caught” or “incapacitation” to reduce crime we have to 1. Make an arrest and 2. Secure a conviction with a meaningful sentence. As MPD’s closure rates and the DC Sentencing Commission’s report makes clear, many violent crimes are falling through the cracks. MPD’s clearance rates tend to be better than the nationwide average (per lagged 2020 data from the FBI) but lower than New York City’s NYPD:

Solving crimes is hard. With more-common masks limiting victim/witness ability to identify suspects, ubiquitous fake vehicle tags hindering vehicle identification, a dysfunctional crime lab and a shortage of CCTV cameras (among other issues) it’s harder to solve crimes both post-COVID and in DC specifically. DC’s murder/homicide closure rate has been trending down in recent years and is now at its lowest since 2015. It’s important to note that even NYPD-level closure rates still leave some crimes unsolved. While we should try to improve here in DC we’ll never get to 100% clearance rates.

One key caveat about DC’s clearance rates is that they are averages and obscure variation between different situations. For example, in many domestic (i.e. spouse or partner) homicides or assault with a dangerous weapon (ADW) the suspect is relatively obvious and is often arrested relatively quickly. In contrast, gang/crew-related violent crimes often feature experienced criminals and victims who won’t cooperate with police and therefore these cases can be much harder to solve. We don’t have publicly-available granular data to see if gang/crew-related offenses have lower clearance rates but given the geographic disparities in closure rates (from MPD’s oversight responses) I suspect that is likely:

When I manually reviewed homicide arrest rates it appeared that wards 4, 7 and 8 had lower arrest rates. The concern is that closure rates are likely a bit lower for the gang/crew-related shooters that are the biggest drivers of gun violence and a result they are less deterred from violence.

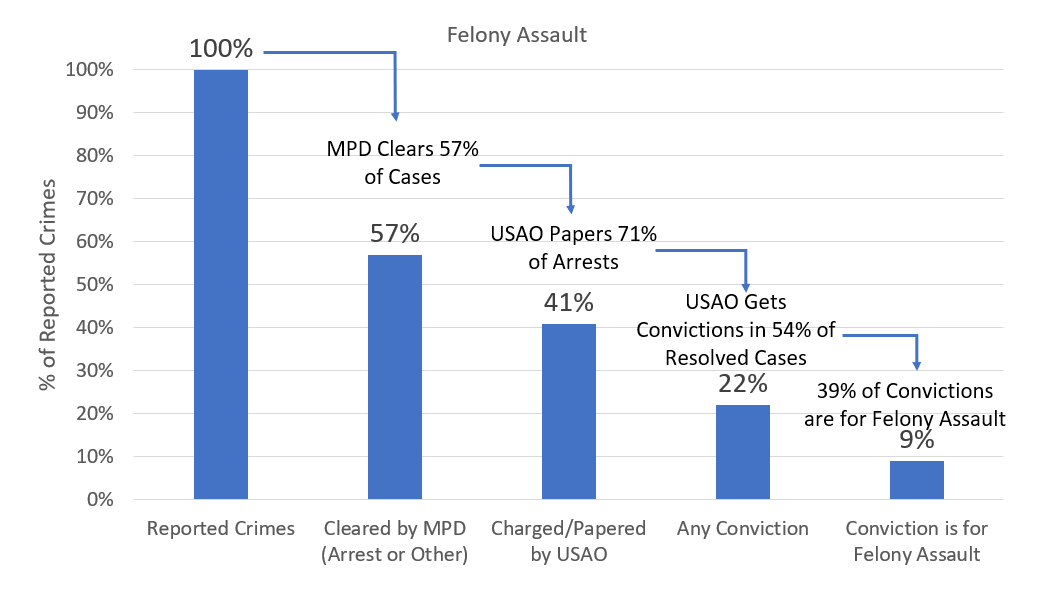

As we’ve discussed many times, after an arrest the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO) decides if they want to press charges (“paper” the case). For serious violent crimes the USAO does paper most cases but even here a significant minority of felony assault cases are never being charged (and this has been increasing):

This DC Sentencing Commission Report for FY 2022 is the most recent data source I can find that tracks how these crimes are being handled in the justice system. Notably it does include the huge decrease in arrests that began during COVID but it mostly missed the large increase in carjackings that has accelerated after this report was published.

Post-COVID, the arrest volumes for these three serious violent crimes are under 600 a year or less than 4% of MPD’s annual arrests. ~600 arrests (some of which may be the same person twice and not all are DC residents) would be about 0.1% of DC’s population and in the same ballpark as the CJCC’s estimate of 200-500 persons driving 60-70% of shootings in DC. This is worth highlighting because vigorously solving and prosecuting serious violent crimes does NOT have to be the same thing as “mass incarceration.” There is a lot of well-founded concern about turning to more incarceration for minor crimes. It’s important to focus both in policy and messaging on this very small number of criminals driving violent crime.

Even when the USAO does press charges, it is still often very difficult to secure a conviction. These cases can take a very long time (and COVID delays stretched many of these cases out); putting (potentially) high-risk suspects under Pretrial Services Agency (PSA) supervision for lengthy periods of time. Because of the high volume of cases that are still pending it’s difficult to gauge the USAO’s true “win rate” for these cases. Below is the “Conviction %” among both all cases and only those that were resolved:

Obviously no one expects the USAO to “win” every case. DC has excellent public defenders who are able to leverage the Brady list, DC’s crime lab problems and other shortcomings of DC’s law enforcement ecosystem to poke holes in cases. However the USAO’s violent crime conviction rates are well below the DOJ Strategic Plan’s target of 90%:

The 90% target is for USAOs across America and the DC office is in the unique situation of being the only prosecutor for most local (adult) crimes. So the DC caseload is likely different from other offices but this suggests that higher violent crime conviction rates are possible. This would be a very interesting avenue for journalists to compare DC’s USAO-led performance to other cities who have their own prosecutors.

When the USAO does secure a conviction in these serious cases it’s often for a lesser crime than the original charge. This is most common in felony assault and least-common in homicides. The USAO’s 54% “conviction of resolved cases” rate for felony assault includes a large number of plea bargains that only ended in a misdemeanor. Compared to a felony assault conviction, these suspects receive much lighter sentences, they will be relatively “lower risk” for pre-trial release on any subsequent charges and their criminal history score will be lower for sentencing in any subsequent convictions:

I strongly suspect that the relatively large share of felony assault suspects who are either no-papered, dismissed or received a misdemeanor-only plea bargain contributes heavily to the perception (and reality) of MPD playing “catch and release” of “bad guys with guns.”

There is research that suggests that the higher priority that police departments give to homicides over non-fatal shootings is a key driver in higher closure rates for homicides: “We find the large gap in clearances (43% for gun murders vs. 19% for nonfatal gun assaults) is primarily a result of sustained investigative effort in homicide cases made after the first 2 days.” In many cases the difference between a gun homicide and a non-fatal shooting is only a matter of luck and the extra effort/resources that went into solving homicides actually yielded more closures. MPD has a relatively small gap between homicide (62%) and ADW (57%) closure rate. However it’s possible that a similar resourcing prioritization at USAO contributes to the USAO’s much higher papering rate (91% vs. 71%) and somewhat higher conviction rate (62% vs. 54%) for homicide vs. felony assault. Since previously no-papered or not-guilty felony assault suspects often become homicide suspects it’s possible that more USAO resources dedicated to the felony assault cases could help secure convictions and “incapacitate” these suspects before they kill someone.

If we compare how these cases are handled throughout the entire process we see that homicides are 3X as likely to end in a serious conviction as felony assaults:

The gap is not as large (but still meaningful) in terms of securing any conviction with 56% of homicide arrests and 39% of felony assault arrests ending in a finding of guilt. Note that these graphs are slightly different from some previous Tweets since I’m using the “conviction % of resolved cases” rate to be as generous as possible to the USAO. Since each step in the process is multiplicative any changes (up or down) in any stage “snowball” into a larger impact. For example, if the USAO papered and won felony assault convictions at the same rate that they paper and win homicide convictions, then each year you would have 87% more felony assault convictions without MPD solving any more cases. And if MPD could raise its closure rate to be closer to NYPD’s then DC could raise that even further.

The point here is not just to raise numbers on a graph. These are serious crimes that represent a tiny fraction of overall crime in DC but a significant trauma for victims and a huge share of the public’s anxiety. Solving more of these crimes (more on that in a future post) is objectively good. Securing convictions and meaningful sentences to keep this incredibly-small population of violent criminals from harming other Washingtonians is worth the (significant) cost of their incarceration. With felony assault most of these crimes are in Groups 4-6 in DC’s Sentencing Grid (see page 78) where probation-only sentences are not an option, first-time offenders face 1.5-10 years in prison and average sentences for ADW are 46 months (3.8 years). But plea bargaining down to misdemeanors puts many of these defendants in group 8 where probation-only sentences are allowed and much more common. And of course defendants that are no-papered or dismissed are not “incapacitated” at all. Working on these policing and prosecution gaps in the system should be a much higher priority for DC’s political leaders than tweaks to sentencing guidelines.