The rhetoric and reality of DC's prosecutors

Lack of transparency lets prosecutors say one thing and do another

Prosecutors are one of the most important parts of DC’s criminal justice system. Their decisions about which cases to charge and how to conduct those cases have a huge impact on public safety. Prosecutors also play a key advisory role in crafting legislation; though sometimes their rhetoric doesn’t match their actions. Both the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO) and the Office of the Attorney General (OAG) have been active in drafting and commenting on legislation while their own contradictory actions are largely hidden from the public.

Rhetoric: The USAO generally uses “tough on crime” rhetoric and consistently supports longer sentences, more authority for searches and more pretrial detention for the adult cases they prosecute.

Reality: The operational reality is that the USAO declines to prosecute far more cases than other adult prosecutors or even DC’s juvenile prosecutor (the OAG). The USAO also appears to prioritize maximizing “convictions” through generous plea deals with little or no prison time instead of trying to secure longer sentences for violent criminals. The USAO is not nearly as “tough on crime” in practice as they present themselves to the public.

Rhetoric: The OAG under both Karl Racine and Brian Schwalb generally use more rehabilitative rhetoric about their juvenile cases and often support less carceral approaches like diversion and restorative justice programs. Politically this has led some voters to regard the OAG as “soft on crime.”

Reality: The OAG prosecutes a larger share of MPD’s arrests than the “tough on crime” USAO; with that rate increasing significantly over the past years without the same kind of media/Congressional pressure that brought change to the USAO. The OAG’s latest data also indicates that they secure more prosecutions and use less diversion than the USAO.

Thanks to data obtained by Jonetta Rose Barras via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request we finally have some recent prosecution data for DC’s Attorney General. Over the first 9 months of 2023 they have “petitioned” (i.e. decided to prosecute) 56% of the juvenile arrests that MPD brought to them. This data point inspired me to review the OAG’s performance oversight responses and it turns out that previous years’ prosecutions rates were there all along without drawing much attention:

This helps us track the OAG’s prosecution rate and compare it to the USAO:

The OAG’s current juvenile prosecution rate of 56% is 12% higher than the USAO’s FY 2023 average and still 3% higher than the USAO’s most recent quarter.

It’s hard to compare adult and juvenile crimes but if anything one would expect an adult prosecutor to be more eager to bring charges.

The OAG’s juvenile prosecution rate is lower than the data they shared with the Washington Post where they “declined to prosecute just 26 percent of its cases.” It’s possible that the OAG’s non-juvenile prosecution rate is higher to explain this gap but it would be best if the OAG could explain the difference.

The OAG’s prosecution rate has risen materially in recent years from incredibly low (33%-35%) levels. Notably this increased prosecution rate happened without the same kind of intense media/Congressional pressure that drove increased USAO prosecution rates.

The OAG’s gun possession prosecution rate of 80% is much higher than the USAO’s ~55% rate for these kinds of crimes. This data confirms MPD officer anecdotes that the OAG is more eager to press firearms charges than the USAO. This also contradicts the USAO’s claims that they couldn’t prosecute more of these gun cases due to MPD officer actions and adverse court rulings. It’s worth noting that most of MPD’s adult arrests for the most common firearms charges don’t result in a conviction.

This is one reason that I have concerns about some parts of the ACTIVE Act:

Currently the bill treats people accused of gun crimes on pretrial release the same as those convicted of gun crimes in terms of expanding MPD’s powers to search them in public. Since many gun cases don’t end in a conviction, these conditions would end up being imposed on some people that are never actually found guilty. The rationale (and possibly judicial precedent) for applying these search conditions to people convicted of a crime is much stronger.

Since the US Marshals/MPD are often not even enforcing bench warrants for people violating their release/probation it is extremely unlikely that they have the bandwidth or ability to target these searches to the specific people meeting the conditions of the ACTIVE Act.

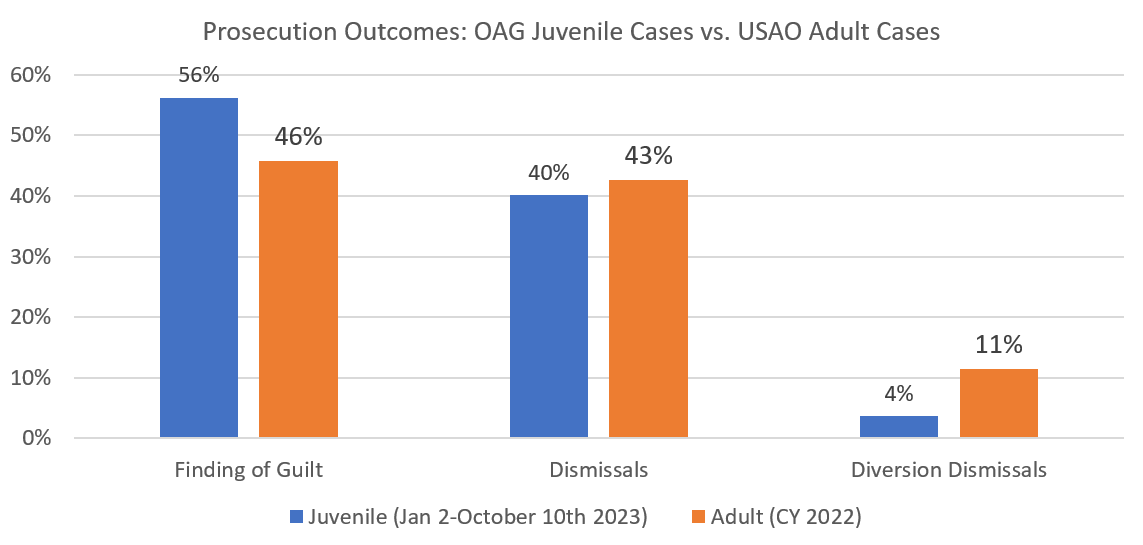

This dynamic where the OAG is generally a “tougher” prosecutor than the USAO appears to carry over to case outcomes. In the FOIA’d OAG data most of the petitioned cases are still pending in the courts; but those that have reached an outcome were more likely to have a “Finding of Guilt” than the USAO’s most recent data. The USAO was also more likely to dismiss cases (either outright or as part of a plea deal) and to dismiss cases after completing diversion:

It is fundamentally ridiculous that our only insights into prosecutions in DC come from FOIA requests, annual performance oversight questions and annual reports from DC Courts and the USAO. The point of these comparisons isn’t to argue that the OAG is doing it “right.” Washingtonians deserve more frequent and granular data from the OAG and apples-to-apples comparisons with other cities’ prosecutors to make an informed judgement on that question. But this data does help illustrate that anyone who thinks the OAG is too “soft” on crime should be even more concerned about the USAO. There are plenty of people that are equally critical of the OAG and USAO and that is a consistent position. But there are many commentators (especially the Mayor’s supporters) who overwhelmingly criticize the OAG (dating back to the Mayor’s feud with then-AG Karl Racine) for being too soft on juvenile crime while largely ignoring the USAO’s practices. Since last year there were about 8 times more adult arrests than juvenile arrests; the USAO has a proportionally larger impact on crime than the OAG.

Another aspect of prosecution where the USAO’s actions don’t match their rhetoric is in how they negotiate plea bargains. In pretty much every jurisdiction most convictions come via a plea bargain and DC is no different. But prosecutors have a lot of discretion when offering plea bargains. What we see in the sentencing data is that the USAO often offers plea bargains for much less serious charges; knowing that will result in little or no prison time for even violent offenses. Before we dive into the data it’s beneficial to review the USAO’s philosophy of sentencing. Here is part of their testimony in favor of the Mayor’s “Safer Stronger” bill:

The USAO cites two key points:

The certainty of punishment is “a vastly more powerful deterrent than the punishment.” This is thoroughly backed by research and is why looking at the USAO’s prosecution and conviction rates (as well as MPD’s case closure rates) is so important.

The public safety benefit of “lengthy sentences” comes from “incapacitation.” This refers to preventing offenders from committing new crimes (in the community) by incarcerating them. The benefit of incapacitation is directly proportional to how likely the offender would be to commit new crimes (and the severity of those crimes) if they were instead given a shorter sentence. There is little public benefit (and significant cost) to incapacitate a low-risk offender.

One dynamic is that incapacitation has less crime-fighting benefit when the probation system (in DC’s case, the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA)) is effective at rehabilitating people and preventing recidivism. For people seeking to minimize crime and incarceration, making CSOSA function well is an imperative.

Broadly speaking this stated philosophy makes sense. The crimes where an incapacitation approach makes the most sense are in cases of violent crimes and firearms offenses given their severity and the higher risk of recidivism for those offenses. However, when we look at the USAO’s actual convictions in Felony Assault crimes (Assault with a Dangerous Weapon (ADW), Assault with Intent to Kill (AWIK), and Aggravated Assault) we see almost the opposite of an incapacitation approach:

61% of all convictions are for other, less serious crimes than any of the Felony Assault Offenses. Recall that all of these cases were originally charged as Felony Assaults.

The vast majority (70%) of these lesser convictions were for misdemeanors

Of the 39% of convictions that were for a Felony Assault Offense, the majority of them were for “Attempted” Assault With a Dangerous Weapon (ADW).

“Attempted” ADW carries a sentence that is usually 1/4th that of actual ADW

Almost all of the “Attempted” ADW convictions were the result of plea deals; not due to the facts of the case only supporting an “Attempt” charge.

Robbery (the most common violent crime) shows a similar pattern where 46% of all convictions were for “Attempted” robbery in 2022. There has been a shift towards “Attempted” offenses (that have much shorter sentences) across the entire violent crime category:

This trend towards more lenient plea bargains was happening at the same time the USAO was declining to prosecute a larger share of cases. One would expect the remaining share of cases they did prosecute to be more serious. If that was true (and it is certainly how the USAO has defended its low prosecution rates) we don’t see any evidence of the case severity increasing in the sentencing data.

Because 97% of the USAO’s 2022 convictions were the result of guilty pleas, we can safely say that the decision to agree to these lesser charges largely rests with the prosecutor. As shown in the table below, similar situations can be charged with different offenses that come with very different likely sentence lengths. Prosecutors need to offer something in a plea deal but they are often choosing to jump all the way down to the most lenient possible charges:

I highlighted the crime “Possessing a Firearm During a Crime of Violence” because it is directly relevant to DC’s fight against gun violence. This is a crime that carries a 5 year mandatory minimum and applies to violent crimes where the offender uses (possesses) a gun; which in 2023 has been 64% of all violent crimes. Even though violent crime with guns is up 91% above the pre-COVID baseline, convictions for this charge are down; from a high of 150 convictions in 2014 to just 34 in 2022. This also represents a shrinking share of the USAO’s weapons convictions:

The end result of all of these trends is that even when the USAO secures a violent crime or weapons conviction, the sentences are shorter than they were a decade ago:

In a recent poll 80% of DC voters supported "longer sentences for violent crimes." The specific intent of that poll question was probably to demonstrate support for the various “sentencing enhancements” that the Mayor and CM Pinto have proposed with the USAO’s support. But this data from the Sentencing Commission shows that by far one of the biggest impacts on sentence length is the USAO’s discretion (alongside the judge’s discretion in sentencing). As we’ve seen, DC has laws that provide for “longer sentences for violent crimes" but prosecutors are often eager to quickly secure a conviction (or “win”) through a plea deal for a much lesser charge.

To explain why this happens one MPD officer claimed “An assistant united states attorney has said that if the case looks moderately challenging, they won't pursue or will offer a plea.” That kind of anecdote seems a lot more credible when:

We have seen the USAO decline to prosecute vastly more cases when compared to other cities or even DC itself a decade ago

We know that the Department of Justice has a goal to “Favorably resolve 90 percent of federal violent crime defendants' cases" which if applied to the USAO in DC would pressure them to avoid tough cases and offer more generous plea deals to secure convictions.

All of the USAO’s media incentives are to minimize losses. There’s almost never any negative media attention towards plea deals and only recently was there any focus on prosecution rates. But losing a violent crime trial is much more likely to generate negative press. All of the USAO’s behavior aligns with these media incentives.

For everyone that has staked their crime-fighting strategy primarily on “incapacitating” violent criminals this sentencing data ought to be a wake up call. Even though the USAO will consistently testify in favor of “tough on crime” legislation (and generally validate the Bowser administration’s talking points) that does not mean they are living up to their promises to incapacitate violent offenders. Hopefully this will rouse some of DC’s “tough on crime” politicians to better hold the USAO accountable.

We also shouldn’t forget about the OAG. We’re only able to scrutinize the USAO’s plea bargaining because of reports from the DC Sentencing Commission. We don’t have any kind of public-facing equivalent data source for the OAG’s juvenile cases. The Mayor and Council should look into how the public could have a common, monthly view of adult and juvenile arrest, prosecution and sentencing data. Many other cities have this kind of data and it helps drive accountability throughout the system. We now know in hindsight that there were massive changes in how DC prosecuted crimes (both adult and juvenile) over the last few years with almost no transparency to the public or even most policymakers. We can’t allow ourselves to get caught off guard again.

The bullet comparing OAG and USAO prosecution rates should probably read "of 56% is 12% *percentage points* higher than" as I think it's comparing 44% to 56% as shown in the chart below the text.

Also, a wise man once wrote to the DC Council and said "when certain crimes of violence are committed by using or displaying a firearm, there should be a **5-year minimum penalty** [bold in original] for that offense."

https://www.scribd.com/document/607568374/Council-of-DC-RCCA-10-20-2022-1

What is your analysis of the incentives USAO has to be less effectively "tough" on crime than their rhetoric or the past?