One of the most basic and consistent findings in criminology research is that increasing the certainty that a criminal is caught is by far the most effective way to deter criminals for committing more crimes. Unfortunately the vast majority of DC’s crime debate is instead focused on what to do after an individual has been arrested, charged and convicted. With few (and recent) exceptions, the share of crimes that are solved by police is taken as a fixed constant by policymakers rather than as a key lever in the fight against crime. While individual MPD officers and civilians are doing everything they can to solve crimes (often at great personal sacrifice) there are systemic best practices from other cities that could make MPD more effective as a whole.

Unfortunately MPD has been solving a smaller % of crimes in 2023, which in turn weakens deterrence. Clearance rates (the % of crimes closed via an arrest or “extraordinary” means) have declined both for crimes that are up in 2023 (homicide, robbery) and those that have remained relatively flat like ADW. Note that MPD didn’t report a clearance rate for “Non-Fatal Shootings” in CY 2022 so we don’t have a trend:

Criminals are obviously not looking at the exact clearance rate percentage before deciding to commit a crime. But their general sense of “I could get away with it” is responsive to large changes in clearance rates like when robberies (up 70% YTD) go from resulting in an arrest 1/3 of the time to just 1/4 of the time. Seeing other people get away with crimes is one reason that the “Kia Challenge” drove a massive increase in Motor Vehicle Theft across America (up 91% YTD in DC). Since the likelihood of getting caught is the key deterrent to crime, if it weakens it can cause a negative feedback loop:

Clearance rates fall in a given area (city, ward, neighborhood etc.) or for a particular crime

Criminals notice that they can “get away with it” and both engage in more crimes and/or shift their criminal behavior to that vulnerable area

The increase in crime makes it harder for police to "keep up” which further drives down clearance rates and repeats the process in step 2

This is a massive simplification of the many reasons criminals choose to commit crimes but it illustrates how falling clearance rates themselves can contribute to increases in crime. What we want instead is a positive feedback loop where a high certainty of getting caught deters crime, reduces the workload on police (giving them more time to devote to each crime) and makes criminals more likely to take the “off ramps” that social programs, Violence Interrupters etc. offer as alternatives to crime.

One driver of the clearance rate is simply the volume of detective resources allocated to solving a particular type of crime or crimes in a certain area. Solving crimes can take a lot of work (criminals have many tactics to avoid detection) and there’s extensive research (cited by both Liberal and Conservative organizations) that when police increase the resources dedicated to solving crimes that they can increase clearance rates dramatically:

“The BPD [Boston Police Department] homicide unit cleared about 47% of homicides during 2007–11. During 2012–14, when the project reforms were implemented, some 66% of homicides were cleared. In the latter years, homicide clearance rates in the U.S. remained flat while Massachusetts homicide clearance rates dropped. An analysis that controlled for case characteristics found that the changes led to a 23% increase in homicide clearance for cases investigated.”

In 2023 YTD MPD’s homicide clearance rate is 41% (though was over 60% in recent years)

“The Denver Police Department, for example, created a special unit to investigate nonfatal shootings with the same level of effort as homicides. In the first seven months of 2020, the unit solved 65% of the city’s nonfatal shootings, a dramatic improvement over the department’s previous 39% nonfatal shooting rate.”

In 2023 YTD MPD’s nonfatal shooting clearance rate is 22%

One way to assess how police departments allocate resources to solving crimes (vs. other law enforcement duties) is what percent of the total force is in detective roles. All police officers can help solve crimes but detectives are a critical and specialized resource. A law enforcement source encouraged me to compare MPD to other cities and relative to New York City we see an interesting correlation:

The NYPD allocates a significantly higher share of its officers to detective roles

The NYPD has significantly higher clearance rates for violent crimes

New York City has much lower violent crime rates than DC

Given the research and common sense it makes sense that this greater investment in training and retaining detectives has delivered higher clearance rates in New York City. If MPD had a similar allocation of officers to detective roles as NYPD, that would mean about an additional 200 detectives (increasing the detective force by 67%) to help solve crimes. That would almost certainly have a material impact on clearance rates and deterrence. Training detectives takes time and shifting any number of officers to detective assignments then creates holes elsewhere in MPD so this is a question of tradeoffs. My assessment of the research is that building up the detective force is a winning tradeoff for MPD and one where we have other options to mitigate the downsides (which I’ll discuss below).

We’ve also seen a correlation in DC between lower homicide clearance rates and MPD shifting funds disproportionately out of the Homicide Branch:

While “MPD has proportionally fewer detectives and that is likely reducing clearance rates” is a helpful finding it’s not a plan. However there are concrete steps in the near-to-medium term that MPD could do to solve more crimes and increase deterrence:

1. Expand detective training and reallocate officers:

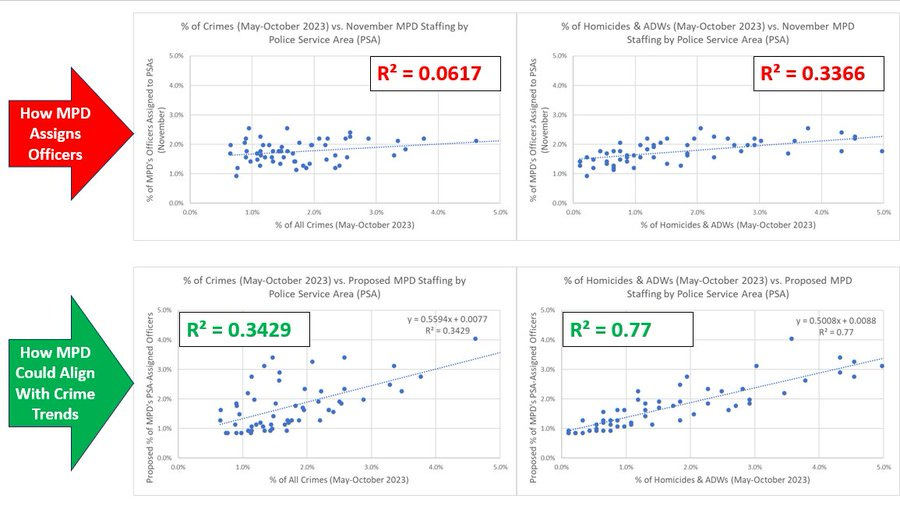

Given the research, it makes sense to prioritize training more detectives and having more officers assigned to investigative roles to assist MPD’s current detectives. Detective roles tend to be appealing to officers so the binding constraints would likely be 1. The number of training slots and 2. The number of high-performing officers other MPD leaders will tolerate going to Assistant Chief Heraud’s Investigative Services Bureau (ISB) at the expense of their own staffing. Both constraints could be addressed if Chief Smith made this a priority. One way to lessen the operational sting of losing some officers to ISB and also further deter crime would be by reallocating patrol officers to where they are most needed. MPD’s staffing still has almost no correlation with overall crime rates and shifting officers to the highest-crime areas (like the simple model I built in this post) would align with best practices like Hot Spot Policing:

Lastly, MPD has to devote significant police resources to handling protests and other activities in the vicinity of the Capitol. If federal agencies like the Capitol Police and Park Police took over those duties (reliably) that would free up many MPD officers to either backfill patrol roles or shift to investigative roles. If anyone in the Department of Justice or Biden administration is reading this, that would be a direct and significant way the federal government could help MPD fight crime.

2. Leverage civilians:

One of the ways most large police departments help maximize their officers’ effectiveness is by hiring civilians in “helper” roles. Unfortunately, MPD is an outlier in having proportionally fewer civilians (often called “professional” staff as opposed to sworn officers) than other police departments: “only 13.2% of MPD’s employees were part of the professional staff, well below the 2019 national average of 22.2% for full-time law enforcement employees within the nation’s cities.” While the Mayor correctly called for “civilianizing” some roles to free up officers for core police duties, over the last fiscal year MPD only had a net gain of 21 civilians. Of the many civilian roles in MPD here are 3 types that are most relevant to the question of “how do we solve more crimes and backfill officers?”

Criminal Research Specialists: This role is incredibly important to solving crimes. These civilians help pull together information across the many systems and sources MPD has available (CCTV, GPS, LPRs, criminal databases etc.) to directly support detectives. It pays $72K-$92K a year and does not require a college degree. Ramping up hiring for this role ought to be a top MPD priority.

Community Safety Ambassadors (CSAs): These civilians handle low priority and non-emergency calls for service (like parking, littering, vandalism complaints), administrative tasks and “Safe Passage” kind of work. “CSAs help to free up police officers to focus more on crimes requiring an armed response.” This role is a great complement to MPD’s sworn officers who otherwise have to spend a material amount of their limited time on these lower priority tasks. MPD opened up this role in the Summer but its unclear how many of these positions they have managed to fill so far.

Admin Roles: These vary but there are still over 200 sworn officers in parts of MPD where probably more of the work could be handled by civilians (HR, Internal Affairs, the Academy etc.) It’s completely appropriate for MPD to have sworn officers in some administrative roles but given how much lower MPD’s use of civilian roles is than other departments it’s likely there is some remaining opportunity here. I will note that since I first wrote about these admin roles in March there has been a shift of ~50 officers out of these positions which suggests that MPD has been working on this issue.

3. Use technology and financial resources:

In many ways DC is behind the curve in crime-fighting technology. The upside here is that we have the opportunity to simply copy existing best practices to get real improvements by “catching up” without having to do expensive (and unproven) innovation. To Chief Smith’s credit she seems to prioritize learning from other cities:

The quote above is from a story describing the upcoming launch of DC’s “Real Time Crime Center” to provide 24/7 monitoring and coordination with other jurisdictions and federal law enforcement. This is a good step forward and the main criticism is why it took a violent crime spike in 2023 and new leadership at MPD for the Bowser administration to implement best practices from other cities. There are other areas where MPD has fewer tools than other departments:

The NYPD has about 60,000 CCTV cameras while MPD has ~330. Even adjusting for DC’s smaller population, NYPD still has a far higher density of cameras. Especially with DC’s non-functioning crime lab, a disproportionate share of the crimes MPD does solve are due in large part to surveillance camera evidence.

NYPD security cameras have had facial recognition since 2011, MPD’s cameras apparently do not

MPD officers will often complain about the quality of the images from their CCTV cameras. Anyone who has seen the images they release to the public would likely agree that they are not state of the art.

MPD only had 63 License Plate Readers (LPRs) as of their Spring performance oversight responses and they had not added any in Fiscal Year 2022. This is an important technology to track stolen vehicles and better-quality LPRs can also provide images of the driver and passengers to help detectives link suspects to a vehicle.

Many police departments are now using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs or “drones”) to help respond to 911 calls, shooting alerts and other emergencies. We’ve seen them be useful in jurisdictions like New York and even here in the DMV in Montgomery County, Maryland. I plan to write a full post about this topic but in short UAVs are safer and more effective to track stolen cars than a dangerous vehicular chase and vastly more cost efficient than a helicopter pursuit.

Lastly, simply increasing financial rewards for tips seems to have some small positive impact on solving crimes. MPD increased the reward for tips related to illegal firearms and it increased the number of useful tips that came in.

With most of these technologies and approaches there are legitimate concerns about surveillance. The fact that these systems have been in use in other jurisdictions gives us a template for the kinds of laws and policies needed to strike the right balance. Chief Smith’s Strategic Plan update and her steps to launch the Real Time Crime Center all indicate that her team is embracing technology. Unfortunately it seems like under Mayor Bowser’s past MPD chiefs DC was allowed to fall behind other cities and this has likely made it harder for MPD to solve crimes today.

These three efforts are all non-ideological, technocratic ways that MPD could solve more crimes and therefore better deter crime. But there’s also a human element to policing. A reader flagged these comments by Assistant Chief Kane at a recent town hall event:

“The Chief alluded to what occurred in 2020 that really shifted how our officers kind of [unintelligible] up. And so getting them back in the game that has really been a big push from the Chief right down to the the executive command staff and to the management that we have on the street. And so at this point what we’re really doing is rebuilding their confidence back up, right? They were beat down just a little bit. So we’re rebuilding their confidence back up, and the more they see that they’re supported, the more they see that we’re out there with them, the more work that they’re gonna do.”

These are pretty amazing comments (especially the last sentence) to hear from one of the most senior leaders in MPD. She’s implying that police officers pulled back or did less work in response to the protests after George Floyd’s death (that Chief Smith had alluded to previously). This is surprising because this is a narrative one mostly sees from MPD’s left-wing critics; who allege that some police officers have been engaged in a “silent strike” of not doing their jobs because they didn’t like being criticized. The fact that she also attributed this attitude to MPD officers writ large (rather than a disgruntled minority) would also be seen as deeply insulting to those who have been trying their best regardless of the political climate if it came from anyone outside MPD. I encourage readers to imagine the howls of outrage from MPD, the Mayor and the media if the Attorney General, the Auditor or a member of the Council said anything remotely disparaging the work ethic of MPD officers. However, while this kind of statement is politically incorrect, there’s a lot of evidence to suggest that Assistant Chief Kane has a point.

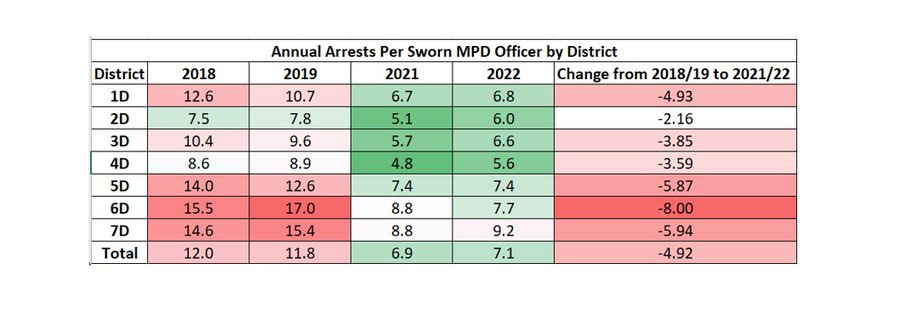

MPD’s arrests-per-officer collapsed during the initial COVID lockdowns and have yet to recover over 3 years later. Arrests don’t correlate 1:1 with clearance rates but a large decrease in arrests almost always corresponds with a lower clearance rate:

Another piece of supporting evidence is that the “pullback” in arrests-per-officer was greatest in police districts 5D, 6D and 7D (basically wards 5, 7 and 8) which have the highest rates of gun violence and due to their racial demographics are the parts of DC most associated with the Black Lives Matter movement. Fewer arrests generally means lower clearance rates and reduced deterrence. Note that by far the smallest reduction in arrests-per-officer was in wealthy and predominantly white police district 2D; lending further evidence to the racial-politics-influencing-policing theory:

Lastly we have the word of MPD officers themselves. When PERF surveyed MPD officers the statement they disagreed with the most was “Employees who consistently do a poor job are held accountable.” It’s notable that this statement scored even lower than things that everyone kind of knows most officers disagree with like “Morale among employees is good” or “Employees are asked for input regarding decisions that will affect them.” The double negatives here can be confusing so it’s worth reframing as “MPD officers overwhelmingly said “Employees who consistently do a poor job are NOT held accountable.”” This strongly suggests that officers know some of their colleagues are not doing their best and aligns with the phenomenon that Assistant Chief Kane described. One review of MPD on Glassdoor called this out directly: “Most of your coworkers, though, will be happy to let you do the lion's share of the work while they hide in a parking lot.” There are no easy fixes to this kind of dynamic, especially when MPD is terrified of losing officers. Chief Smith leading by example and exhorting officers to get out of their cars is a positive development but it’s unclear if her efforts are sufficient to deal with this alleged problem of morale, motivation and discipline that couldn’t help but have a negative impact on clearance rates and deterrence.

Other jurisdictions like New York City show that a more effective police force solving more crimes and creating a virtuous cycle of deterrence and lower crime rates is possible even in “Democrat run” cities. None of the factors that the Mayor and her conservative allies love to blame for crime (a shrinking police force, police reform legislation, a progressive city council, a police-skeptical citizenry) seem to be decisive in stopping other cities from bringing down violent crime this year. This strongly suggests that MPD has a lot of room to improve its crime-solving capabilities to restore deterrence; independent of the latest flashpoints in the Mayor’s legislative Forever War with the Council. This also illustrates how DC’s fragmented and dysfunctional Local-Federal criminal justice system is holding back DC from seeing the post-2020 recoveries that other cities are experiencing. Chief Smith seems to understand this and the optimistic take is that a more effective MPD combined with increased prosecution rates and better downstream-of-arrest prosecution, enforcement and rehabilitation gets DC back on track. But it will take a lot of work and focus from DC and Federal leaders to address the mistakes of the past years and make that a reality.

Joe Friday, what you're doing is great. Is there any way you can email me so we can discuss the limits of data, especially in DC?

One thing that strikes me is the trailing five year cost of the homicide branch in absolute dollar terms. $21M per year is just not that much money. Why aren't we spending much more on this critical service?

Wonder what the comparable figure over that period is in Boston, too.