House Republicans' Vibes-Based Theory of Crime

An inaccurate narrative in service of a misguided bill

Last week the House Oversight Committee voted to approve the “D.C. Criminal Reforms To Immediately Make Everyone Safer Act.” This bill, which also goes by its very deliberate acronym the DC CRIMES Act, is the latest in a series of bills from House Republicans to change local DC laws with the stated objective of reducing crime. While bill names are often quite twisted in order get a good acronym, it’s notable that this legislation claims it will “immediately make everyone safer” given that none of the bill’s 3 major provisions listed below actually involve immediate enforcement or deterrent actions:

“To limit youth offender status in the District of Columbia to individuals 18 years of age or younger”

“to direct the Attorney General of the District of Columbia to establish and operate a publicly accessible website containing updated statistics on juvenile crime in the District of Columbia”

“to amend the District of Columbia Home Rule Act to prohibit the Council of the District of Columbia from enacting changes to existing criminal liability sentences”

Since DC’s lack of statehood makes us particularly vulnerable to the whims of Congress it’s worth taking this bill seriously. In addition, House Republicans’ rhetoric around this kind of legislation is the perfect distillation of a broader narrative I call the “Vibes-Based Theory of Crime” that has dominated DC’s crime debate. This narrative doesn’t align with DC’s crime data or criminological research but it’s so prevalent (and often unquestioned) that it has largely blocked much-needed discussions about breakdowns in DC’s enforcement and rehabilitation “ecosystem.”

The first major provision of the DC CRIMES Act “targets the District’s 1985 Youth Rehabilitation Act. The law allows judges to grant lighter sentences to young adults under 25 and set their convictions aside if they complete the sentence.” The DC CRIMES Act would lower this to defendants under age 18. The YRA has been a convenient punching bag for US Attorney Matthew Graves but the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council (CJCC) found that the law generally had a small but likely positive impact:

Only 13% of disposed cases (those with a conviction, dismissal, or acquittal) were sentenced under the YRA.

“Specifically, a YRA sentence was significantly associated with fewer rearrests among youth offenders ages 22 to 24”

Those defendants who had their conviction “set aside” after completing their sentence were half as likely to be re-arrested and 1/3 as likely to be re-convicted as other defendants.

This may simply reflect that judges did a better job screening defendants that warranted a “set aside” but it hardly suggest that this practice increased crime as some allege

There are people who have been victimized by defendants who benefitted previously from the YRA. Even when the recidivism rate is lower it isn’t 0% so there will always be examples of defendants who (in hindsight) probably didn’t deserve the benefit of a lighter sentence. But it’s impossible to look at a law that only applies to 13% of sentences and has a neutral-to-positive impact on crime and logically blame it for DC’s troubles.

The second provision of the DC CRIMES Act is actually a good idea! It just shouldn’t be something that Congress forces on the District. Requiring the DC Attorney General to publish online the numbers (not names or identifying information) of juvenile arrests, prosecutions, declinations, felony/misdemeanor sentences etc. for various types of crimes is something that DC should do anyway. We should also require such information from the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO). If anything DC’s leaders ought to be a little embarrassed that House Republicans are leading on crime data transparency; regardless of their motivations.

The third major provision of the DC CRIMES Act is a radical proposal to “amend the District of Columbia Home Rule Act to prohibit the Council of the District of Columbia from enacting changes to existing criminal liability sentences.” This would effectively freeze DC’s criminal sentencing laws in place as of the date the DC CRIMES Act goes into effect (if it were to become law). Ironically, this provision would actually block bills like Secure DC that increase penalties.

The Washington Post had a bit of fun pointing out the disconnect between the Republican rhetoric and recent legislative developments:

““If the D.C. Council is not going to act, Congress does have a responsibility to act in the interest of the District of Columbia,” said its sponsor, Rep. Byron Donalds (R-Fla.). “What this bill does is brings common sense back to the criminal code in the District.”

The timing of the effort was highly curious to Democratic D.C. leaders: House Republicans pushed the legislation forward two days after the D.C. Council passed the Secure D.C. omnibus, a massive public safety package that would enhance punishment for certain crimes.”

It’s worth adding that Congressman Donalds is (falsely) blaming the DC Council for failing to act and then writing a bill to prohibit them from acting. Congressman Donalds also tried to use one of my tweets about the USAO declining to prosecute firearms offenses to blame DC “local government” for the actions of DC’s unelected Federal prosecutor:

My initial tweet about a carjacking suspect with what appears to be at least 3 prior not-prosecuted firearms arrests:

Congressman Donalds tried to use this example to blame “local government” and promote his DC CRIMES Act:

I attempted to correct the record about who is responsible for adult prosecutions in DC:

One shouldn’t assume that a lot of fact-checking goes into Congressional tweets but it is interesting that Congressman Donalds gave up a chance to attack President Biden’s Department of Justice (which includes the USAO) in order to (falsely) blame a lack of prosecution on DC’s local government. From a purely partisan perspective the Biden administration is a much higher priority target for Republicans so there’s some opportunity cost when they try to portray all DC crime as stemming from the actions of the DC Council.

Fellow Republican Congressman Comer of Kentucky, who chairs the House Oversight Committee, fully articulated the “Vibes-Based Theory of Crime” when he gave his explanation for DC crime to the Washington Examiner:

“Though Congress voted to nullify the D.C. Council’s attempt to overhaul its criminal code, and President Joe Biden signed the measure, House Oversight Committee Chairman James Comer (R-KY) said the message the council gave in approving the changes was that criminals could get away with infractions.

“The bad actors in D.C. realized they weren’t going to be held accountable for carjacking and burglary and robbery and things like that,” Comer said in an interview with the Washington Examiner. “And I think that led to a tsunami of crime in Washington, D.C. So that’s when we stepped in to try to right the wrong, and the wrong being irresponsible soft-on-crime and policies that the D.C. Council enacted.”

There are 3 key parts of his theory:

Congressman Comer claims that the Revised Criminal Code (RCC) meant criminals “weren’t going to be held accountable for carjacking and burglary and robbery”

He believes that the Council passing the RCC was a “message” that was received by criminals.

He clearly states that “the message the council gave in approving the changes” is what “led to a tsunami of crime.” The belief that politicians’ “tough on crime” or “soft on crime” messaging (or “vibes” in common parlance) is a causal factor in crime rates is why I’ve termed this the “Vibes-Based Theory of Crime.”

This is a clear, causal hypothesis for DC’s crime surge in the Spring-Summer of 2023. However it doesn’t align with DC’s crime data or criminology research and is instead best understood as a political narrative designed to advance political objectives. The first fatal flaw of this theory is how it presumes DC criminals respond to political news:

This theory requires DC criminals to be serious enough news consumers that they heard about the Council passing the RCC in November 2022 and interpreted it as a “message” to go commit crimes even though it hadn’t gone into effect (so they would have zero first-hand experience with its changes).

This theory simultaneously requires that these same news-conscious DC criminals somehow missed the wall-to-wall media coverage of the RCC’s repeal by Congress. Since most of the increase in crime happened after the RCC was repealed on March 20th, 2023, for this “message” to have caused the increase we have to pretend that criminals didn’t receive the countervailing “message” from Congress’ repeal.

The population of people in DC who did hear about the RCC passing but did not hear about Congress overturning it would have to be miniscule given the enormous media focus on the repeal.

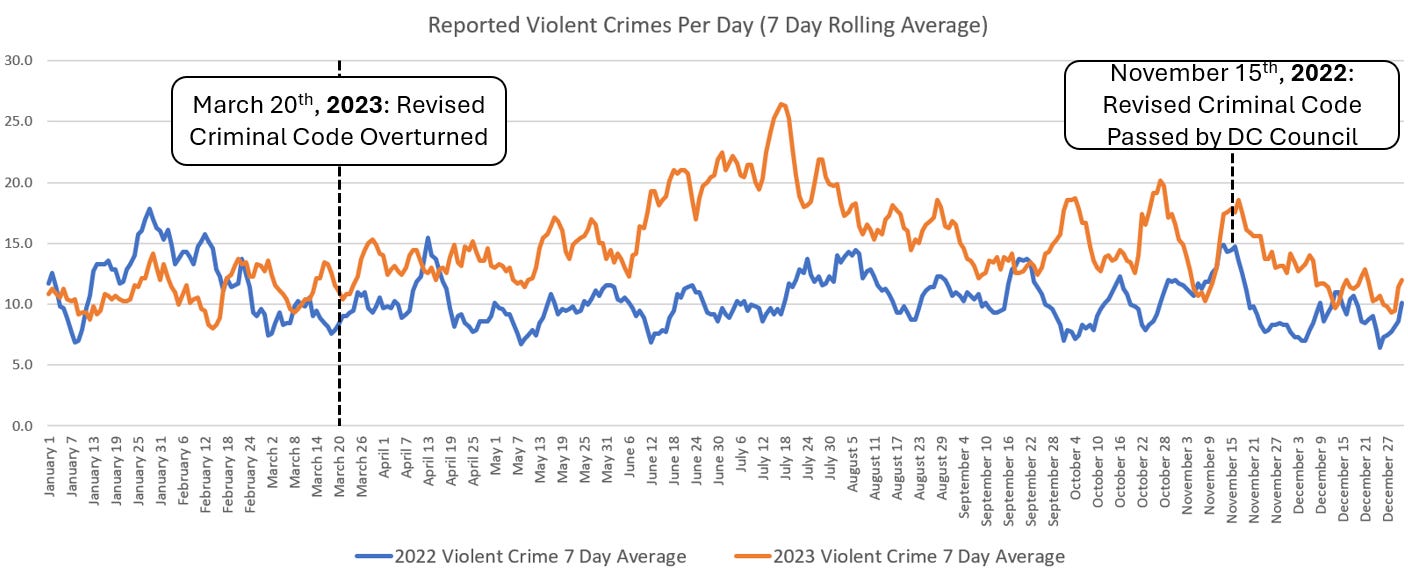

The timing of this alleged “message” to criminals doesn’t make any sense either. After the Council passed the Revised Criminal Code on November 15th, 2022 violent crime rates fell for the rest of 2022 (blue line on the graph) and remained low through mid-February of 2023 (orange line on the graph). The House voted to overturn the RCC on February 9th, 2023, with the Senate voting to do so on March 9th, 2023 and President Biden signing the bill on March 20th, 2023. Violent crime rates in DC only spiked after the RCC was overturned. Congressman Comer’s theory that “the message the council gave in approving the changes” is what “led to a tsunami of crime” doesn’t align with the crime data at all:

Of course people shouldn’t take this all the way to the other extreme and say “repealing the RCC caused the crime spike” but that at least would have some correlation on its side. One reason we shouldn’t be surprised that Congressman Comer’s theory doesn’t explain changes in crime rates is that its focus on sentence lengths doesn’t even address the primary levers of criminal behavior.

The best summary of the research consensus on deterring crime is from the National Institute of Justice (part of the Federal Department of Justice) called “Five Things About Deterrence.” Below are the main points so we can evaluate how well Congressman Comer’s theory aligns with the research:

The certainty of being caught is a vastly more powerful deterrent than the punishment.

Sending an individual convicted of a crime to prison isn’t a very effective way to deter crime.

Police deter crime by increasing the perception that criminals will be caught and punished.

Increasing the severity of punishment does little to deter crime.

There is no proof that the death penalty deters criminals.

Note that this is still a pretty moderate-to-conservative consensus. It reinforces how important police and prosecutors are in deterring crime. The document also points out that there are non-deterrent benefits of “incapacitation” through prison sentences for some offenders. The implication of this research is that when the real and perceived certainty of being arrested and prosecuted for a crime decreases then deterrence weakens and (all things being equal) we’d expect crime to increase.

But notably the research consensus says that criminal perceptions of the severity of punishment “does little to deter crime.” Given that the debate over the RCC was almost entirely about the severity of punishment it doesn’t make sense that criminals would immediately respond to some reductions in the statutory minimums/maximums by committing more crimes (which again, did not happen after the bill passed in November 2022). Comer uses some language that at first glance sounds like he’s concerned about the certainty of punishment when he said “bad actors in D.C. realized they weren’t going to be held accountable for carjacking and burglary and robbery and things like that” but he is clearly referring to sentencing reductions, NOT decriminalization. The Washington Post specifically discussed the proposed changes to these offenses in their coverage of the RCC:

“For most crimes, including robbery, burglary and carjacking, the new code would lower maximum penalties and replace the sentencing range with a new tiered system — which proponents of the bill say would allow for sentencing guidelines to more accurately fit the severity of the offense.

If one defines any reduction in sentencing as not holding criminals “accountable” then we’re clearly talking about the severity of punishment and not the certainty. Especially when these offenses still would have called for years of prison time. And lest we forget, very few accused carjackers are actually convicted of a carjacking offense (due to low conviction rates and plea bargaining) so for the most defendants this argument about carjacking sentencing maximums was irrelevant:

The fact that DC’s crime data confirms that violent crime kept falling for several months after the RCC passed is more supporting evidence that incremental changes in the severity of punishment don’t deter or encourage crime.

In contrast to Congressman Comer’s narrative; when I tried to explain the rise-and-fall of crime rates in 2023 I tethered my narrative to real, observable changes in enforcement and prosecution and how they likely impacted deterrence and incapacitation:

DC had record low rates of arrest, prosecution and detention at the start of 2023, weakening both deterrence and incapacitation

The exogenous shock of the “Kia Challenge” sent motor vehicle thefts skyrocketing, which mostly went unsolved and unprosecuted, further weakening deterrence. The easy availability of stealable cars also made it easier for criminals to commit more violent crimes as noted by MPD Chief Smith’s oversight testimony. Rising crime overall helped further undermine deterrence as police couldn’t keep up; with large drops in clearance rates undermining the certainty of arrest.

New leadership at MPD and significant pressure on the USAO (and less so on the OAG) increased arrest, clearance and prosecution rates, which helped increase deterrence. At the same time the increased prosecutions resulted in large increases in adult and juvenile detention, increasing the incapacitation effect on DC crime. As this was happening both violent crime and property crime fell in DC.

I can’t prove to an academic standard that changes in enforcement-deterrence-incapacitation caused the changes in DC crime rates. But that narrative at least aligns with the available data and the criminology research consensus; which makes it wildly more plausible than the “Vibes-Based Theory of Crime.” Despite this theory’s lack of evidence, it is appealing to a lot of people because it offers a deceptively easy way to bring down crime. It supposes that if only elected officials would say the right “tough on crime” incantations then magically crime would go down. But Mayor Bowser’s years of tough on crime rhetoric did nothing to prevent the Spring-Summer 2023 crime surge across DC. Councilmember Brooke Pinto’s “tough on crime” rhetoric didn’t stop the Spring-Summer 2023 crime surge at the borders of Ward 2. Years of Republican “tough on crime” rhetoric and policies have left deep-Red states like South Carolina, Alabama and Arkansas with much higher murder rates than “soft on crime” Democratic states like New York and California. In all of those cases politician rhetoric had nothing to do with actual outcomes because criminals largely don’t care what politicians say. Criminals respond to real-world factors like the risk of arrest, risk of prosecution, plea bargains and their current life situation.

I’d like to think that most Washingtonians would say it’s highly unlikely that a revised criminal code that never went into effect caused a rise in crime. I especially think that in 92% Biden-voting DC that if one gave the partisan cue that this theory is one espoused by Congressional Republicans they’d be especially likely to reject it. But a lot of people who should know better have instead convinced themselves that the “Vibes-Based Theory of Crime” is true or pretend to believe this theory because it lets them focus the blame for crime on their political enemies. This narrative is really compelling to people desperate for any quick fix to crime but it has the opportunity cost of crowding out attention on actual problems.

Think of how much attention was focused on fights over sentencing reductions and their associated “soft on crime” vibes from 2016-2022 at the same time that USAO prosecution rates were collapsing without any media attention. Think of how many articles debated if a 2.5% cut to MPD’s budget was “defunding the police” while at the same time arrest rates per officer had fallen 42% without any media attention. The “Vibes-Based Theory of Crime” has worked very well for some political interests but has been a disaster for crime policy in DC.